21. December 2017 | Labour Market, Employment and Social Policy

Longer maternity leave – healthier mothers?

This has been shown in a recent study conducted by researchers from the IAB and the University of Cologne. Based on the introduction of the so called „Erziehungsurlaub“ in Germany in 1979, the study demonstrates that the longer leave duration was associated with a higher incidence of long-term sickness spells among mothers who returned to the labor market.

Maternity leave policies and their reforms

Most OECD countries offer, at a minimum, relatively brief leave periods covering some weeks before and after childbirth, with the primary aim to protect mothers and their offspring from immediate health impairments around childbirth. In addition to offering such short leave periods, many countries run much more generous policies. One such example is Germany, which over the past three decades experienced several expansions in maternity leave. While the more recent expansions were primarily initiated to enhance children’s well-being and the compatibility of child rearing and female employment, (West) Germany’s earliest reform explicitly aimed at improving mothers’ health. This first reform of maternity leave took place in May 1979 and raised the length of paid, job-protected maternity leave after childbirth from initially eight weeks to six months.

Why maternity leave might be related to mothers’ health

Maternity leave durations might impact mothers’ health in various ways. As to a direct effect on health, much of the evidence on the labor market effects of maternity leave suggests that expansions in leave duration delay mothers’ return to work as studies for example by Raphael Lalive and Josef Zweimüller (2009) or by Uta Schönberg and Johann Ludsteck (2014) show. For the time during which they are eligible for maternity leave, young mothers should thus be protected from immediate health impairments resulting from stress caused by the double burden of childrearing and gainful employment. Next to such short-run effects, one may also expect longer-run effects, as lack of protection after childbirth might give rise to adverse health shocks triggering increasingly worse health over a mother‘s life course. Moreover, a later return to work is typically associated with a higher incidence of breastfeeding, which may also affect mothers’ short-and long-term health.

Maternity leave may affect mothers’ labor market success

Mothers’ entitlement to maternity leave may also affect their subsequent labor market success and behavior. The direction of this indirect mechanism is not clear, though. On the one hand, job-protected leave entitlements seem to facilitate higher levels of labor force participation among women with small children and have been shown to increase job continuity with the pre-birth employer. They may thus enable more women to enjoy the health benefits of gainful employment. On the other hand, incentives to postpone one’s return to work, set by very generous maternity leave programs, might discourage mothers to participate in the labor market. This may lead to potential economic disadvantages in the long-run, as time spent out of the labor force may devaluate the individual’s qualification level and lower her earnings. Mothers who took leave from work after childbirth might thus experience an indirect ‘health penalty’. Moreover, women losing their attachment to the labor force might not only face economic but also psychosocial disadvantages resulting in adverse health outcomes.

Types of mothers returning to work

A further channel through which expansions in leave coverage might alter post-birth health outcomes of employed mothers relates to the composition of those who return to work. The key mechanism here is that an expansion in leave coverage may cause different types of mothers to return to the labor market. However, the direction of this effect is not clear a-priori. On the one hand, one might argue that longer leave mandates offer better opportunities to recover from the stresses associated with childbirth particularly for mothers with a poor pre-birth health status. More time off work will also allow these women to better adapt to their (prospective) double role as employee and mother, reducing subsequent work-family conflict and its adverse health consequences. This might encourage especially those who otherwise would have stayed away from the labor market to return to work. On the other hand, more time spent at home may make mothers’ acquired qualifications less valuable in the labor market. This is arguably more relevant for those with a poor health status and might therefore worsen the incentives to return to work for the less healthy ones.

Empirical approach of the study

As the reform in 1979 has been implemented depending on the child’s birthday, the policy change creates a setting which allowed the researchers to assess, first, how changes in maternity leave duration affected mothers’ return-to-work behavior and, second, what the reform’s consequences for returning mothers’ health outcomes were. Overall, the empirical analysis made use of the fact that at least for births just shortly before and just after the new legislation came into effect (in particular: four months prior to/after 1st May 1979), mothers should be comparable in all relevant aspects – except for the fact that the latter were exposed to a different leave duration.

How the reform delays mothers’ return to work

Similar to what has been found earlier for example by Uta Schönberg and Johann Ludsteck in their 2014 study, the researchers first showed based on administrative data from the German Pension Insurance and the Federal Employment Agency that the 1979 leave extension caused mothers to significantly delay their return to work within the first year after childbirth. However, the delay in return-to-work is only of short-term nature, since two years after childbirth a similar fraction of pre-and post-reform mothers returned to the labor market (49 and 51 per cent, respectively).

Long-term sickness of working mothers

To explore whether a longer time spent at home supported the return of healthier mothers into the labor market, the study looked at periods of long-term sickness absence. These capture illness episodes of employees who have been absent due to the same disease diagnosis for more than six weeks.

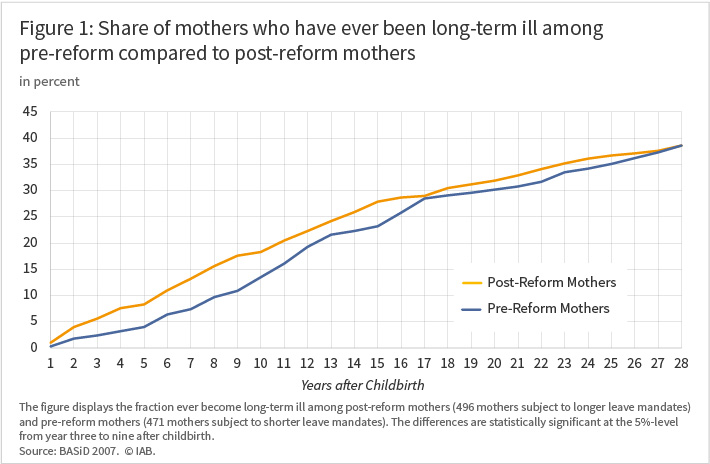

Figure 1 displays the differences between pre- and post-reform mothers in the share of women who experienced at least one long-term illness spell up to 28 years after childbirth. The figure demonstrates that the expansion in leave coverage from two to six months is associated with a larger fraction of women ever having experienced a long-term illness spell. For instance, in year nine after childbirth, the share of women with at least one long-term sickness episode is about seven percentage points higher among post-reform as compared to pre-reform mothers.

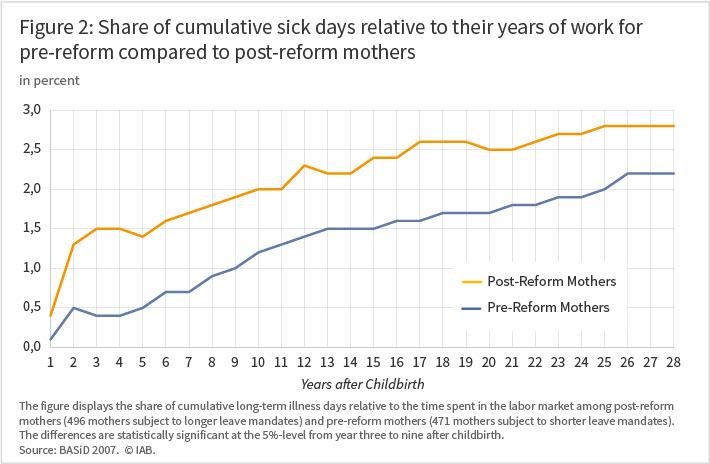

Figure 2 compares the number of days of illness as a fraction of the time spent in the labor market after childbirth across both groups. The figure illustrates that over the whole observation period post-reform mothers experienced a longer duration of illness relative to the time spent in the labor market than pre-reform mothers. Even after about 20 years the difference amounts to nearly one percentage point, suggesting that the difference tends to be long-lasting. Considering the average time spent in the labor market, the figures imply that after 28 years after childbirth post-reform (pre-reform) mothers have experienced on average 141 (131) days of long-term illness. Overall, these findings remain unaltered even if one accounts for the fact that mothers giving birth shortly after and prior to the reform might be characterized by systematic differences, such as their employment histories prior to childbirth.

The overall result of more and longer long-term sickness episodes among post-reform mothers subject to the longer leave duration is clearly surprising and deserves further attention. As argued above, such a finding may be explained by a different composition of mothers returning to the labor market. Put differently, the reform might have encouraged the labor market re-entry of less healthy mothers, who would have stayed away from the labor market under shorter leave mandates.

Health status of mothers returning to work

To investigate this issue, the study distinguished mothers with a “good” pre-birth health (below average sickness absence prior to childbirth) from those with “poor” (above average sickness absence) pre-birth health. After re-investigating the return-to-work effects for these separate groups (details not shown), the results clearly indicate that the return-to-work behavior of both groups was affected differently by the reform: In particular, especially those with a poor health status prior to childbirth increased their return-to-work probabilities after the extended leave duration as compared to mothers in good pre-birth health. One potential explanation for the stronger return-to-work response among mothers in poor pre-birth health is that this group may have benefitted to a greater extent from the legislation’s guaranteed right to return to their old employer as compared to those with a better pre-birth health status. Moreover, the health disadvantage observed among post-reform mothers turned out to be strongly driven by mothers in poor pre-birth health. These results therefore strongly support the view that the reform induced particularly those with a poor pre-birth health status to re-enter the labor market and that the unfavorable health outcomes among post-reform mothers are driven by this group.

Conclusions

Taken together, the evidence suggests that the 1979 reform failed to improve the ”quality” of female labor market participation by supporting the return of a larger fraction of healthier female workers to the labor market. It is important to keep in mind, though, that results from the West German context in 1979 cannot be naively transferred to other countries, such as the United States, where mothers’ attachment to the labor force tends to be higher and maternity leave entitlements continue to be less generous. Still, an important policy conclusion is that the overall effects of expansions in maternity leave on the health composition of those returning to the labor market might be very small (or even negative), if such reforms are not complemented by further measures directed at maintaining or improving working mothers’ health following their return to the labor market.

References

Hochfellner, D., Müller, D., & Wurdack, A. (2012). Biographical data of social insurance agencies in Germany – improving the content of administrative data. Schmollers Jahrbuch, 132, 443-451.

Lalive, R., & Zweimüller, J. (2009). How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? Evidence from two natural experiments. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124, 1363-1402.

Schönberg, U., & Ludsteck, J. (2014). Expansions in maternity leave coverage and mothers’ labor market outcomes after childbirth. Journal of Labor Economics, 32, 469-505.

The study is forthcoming under the title „Maternity leave and mothers‘ long-term sickness absence – evidence from West Germany“ in the journal “Demography”.

Diese Publikation ist unter folgender Creative-Commons-Lizenz veröffentlicht: Namensnennung – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de

Authors:

- Nicole Gürtzgen

- Karsten Hank

Nicole Gürtzgen has been head of the IAB research department „Labour market processes and institutions“ since October 2015.

Nicole Gürtzgen has been head of the IAB research department „Labour market processes and institutions“ since October 2015. Karsten Hank is Professor of Sociology at the University of Cologne and Research Fellow at the DIW Berlin.

Karsten Hank is Professor of Sociology at the University of Cologne and Research Fellow at the DIW Berlin.