16. October 2024 | Education and the Labour Market

Who is most open to lifelong learning? Exploring the role of personality traits and skills

Today, labour market conditions are changing at an unprecedentedly fast pace. Globalisation intensifies competition between workers, while technological and ecological changes disrupt – and may even eliminate – many occupations. As a 2019 OECD study shows, so far, occupations most vulnerable to these changes are characterized by manual and routine tasks which may be easily automated or off-shored, and which are traditionally performed by low-skilled workers. In addition, it is the low-skilled who hold jobs in ecologically damaging sectors, which will shrink in the future in the context of decarbonization, as a 2023 OECD study points out. That is why it is particularly crucial for low-educated individuals to continue professional development, update previously obtained skills or fully retrain. At the same time, it is well-known that low-skilled workers participate in lifelong learning to a lesser extent than their better-qualified counterparts. As shown by Annette Trahms and colleagues in their paper from 2021, low-skilled adults report a significantly lower participation rate in non-formal further training, which rises with increasing level of education.

The literature identifies three main barriers to lifelong learning participation: situation barriers related to individual’s personal and family situation, institutional barriers pertaining to the availability of learning opportunities and dispositional barriers referring to one’s attitudes, personality and expectations (OECD, 2021). This article looks closer at dispositional barriers, in particular in relation to the psychological concepts “Locus of Control” (LoC) and “Big Five”. LoC is a psychological construct referring to the extent to which an individual believes that the occurrences of life’s events are dependent on one’s own behaviour, or are determined by external factors such as faith or luck. Big Five is one of the most popular models to classify the complex structure of an individual´s personality into five main factors. It describes an individual’s degree of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism (for a more detailed description of the concepts, see info box “Personality Traits”).

Personality Traits

The psychological concept of Locus of Control (LoC) measures the extent to which an individual believes in the possession of autonomous control over the events in one’s life. Those with a more internal LoC are convinced that life’s incidents are caused by their own actions and behaviour. On the other hand, individuals with a less internal LoC believe that the influence on their lives is limited and that what happens to them is mostly the result of faith or luck (Rotter, 1966).

The Big Five taxonomy classifies an individual’s nature into five main domains: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. Openness to experience measures the extent to which individuals are open to new occurrences in their lives. Conscientiousness contains the subscales order, competence, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline and deliberation. Extraversion covers the dimensions of social behaviour towards other people and is the opposite of introversion. Agreeableness also contains dimensions of social behaviour such as trust, altruism, kindness and cooperativeness. Finally, neuroticism is the opposite of emotional stability (Costa and McCrae, 1999).

While internal Locus of Control and openness to experience positively relate to further training participation, heterogeneity by skill level is an understudied phenomenon

The impact of LoC and Big Five on the probability of further training participation have been already researched. Marie Laible and colleagues found in their 2020 study that among the Big Five characteristics, openness to experience and extraversion positively relate to the likelihood of participating in further training, while Marco Caliendo and colleagues established in 2022 that a greater degree of internal LoC is linked to more engagement in general training. The positive influence of internal control belief and openness to experience on the training take-up were also shown in two studies from 2013 by Judith Offerhaus and by Didier Fouarge and colleagues.

However, while the link between personality traits and further training participation has been established in the overall population, the importance of different skill levels has not yet been investigated. At the same time, the question seems to be crucial, whether there are any differences in the impact of personality traits on lifelong learning take-up between more- and less-qualified workers. First of all, it may uncover some of the causes behind distinct participation rates of various skill groups in further training. Furthermore, it may help policymakers to decide whether different instruments motivating lifelong learning should be used for individuals belonging to these distinct groups and what the core focus of these policy tools should be.

To tackle this research question, this article uses data from the Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) and focuses on employed individuals aged between 25 and 64 years, as only participation in job-related training is considered. This in turn facilitates an examination of lifelong learning from a labour market perspective, excluding all training measures that are undertaken for private reasons. In this sample, the average participation rate in further training within one year is indeed the lowest for low-skilled adults (10 percent); it increases to around 25 percent for middle-skilled ones and reaches the value of about 40 percent amongst high-skilled individuals. For more information on the definitions of further training, personality traits and skill measures, please refer to the Data and Methods box. The following sections of this article investigate how the training take-up relates to LoC and Big Five personality traits for the respective skill groups.

Weaker relation between internal Locus of Control and further training participation among low-skilled individuals

A simple comparison of LoC between groups with different educational attainment already reveals the existence of prominent disparities. The average LoC score, measured on the scale 1 to 7, for low-educated workers amounts to 4.53, for middle-educated to 4.80 and for high-educated to 5.00. These outcomes indicate that adults with lower education tend to have less internal control belief, meaning that they are more doubtful regarding their personal influence on the events in their lives. This points to the potentially important role of initial LoC for further educational investment, especially given the fact that personality traits are seen as rather stable over the life cycle, as proved by McCrae and Costa in their 1994 study.

Following the work of Marco Caliendo and colleagues from 2022 the initial expectation is that individuals with internal LoC have a higher likelihood of investing in training. That is, workers who believe that there might be a relation between training participation and job-related benefits (e.g. in the form of a wage increase) are expected to engage in further education more than these who doubt that their actions may improve their labour market situation. This phenomenon relates to self-determined training and is indeed observed when comparing workers who took part in learning because of their employer’s encouragement (77 %) and these who did it out of their own initiative (23 %). The mean of LoC is significantly higher in the latter group.

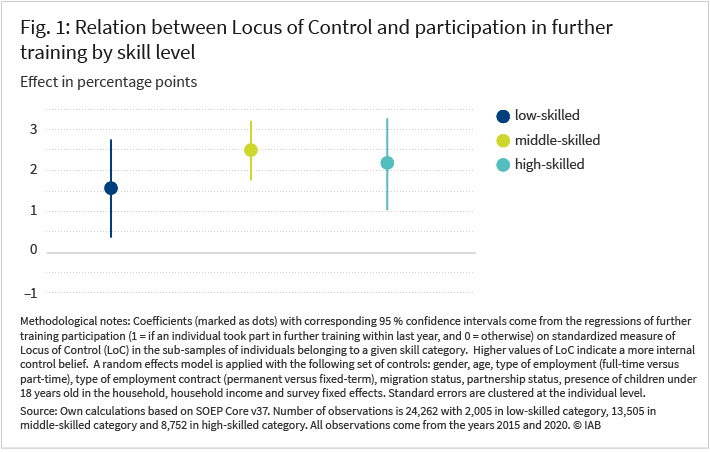

Finally, the regression-based estimates indicate that while holding observed individual characteristics constant, an increase in LoC by one standard deviation (which corresponds to a change by 0.88 points on the scale 1 to 7) correlates with 2.7 percentage points boost in the likelihood that an individual undertakes further training within one year. However, the heterogeneity analysis shows that the strength of this relation differs between skill groups, despite that for all of them it is statistically different from zero. For high- and middle-skilled adults the relation between LoC and further training participation amounts to 2.2 to 2.5 percentage points, while for low-skilled individuals it amounts to 1.6 percentage points (see Figure 1).

All in all, it seems that internal LoC positively correlates with further training participation, but this association is stronger for more skilled individuals. These results suggest that appealing to individuals’ power to control their life in order to encourage involvement in further training, may be only moderately successful in the case of low-skilled workers.

Among low-skilled individuals, only openness to experience correlates with further training participation

Individuals belonging to different skill groups do not differ only with respect to control beliefs. Low-educated adults are significantly less open to experience than their better educated counterparts. The mean of this personality trait, measured on the scale from 1 to 7, for the low-skilled group amounts to 4.58, while for the high-skilled group to 5.03. Differences with respect to this feature are the most pronounced amongst the Big Five personality traits; however, skill groups also differ regarding other characteristics. The degree of neuroticism and agreeableness decreases with increasing educational level. Conscientiousness, surprisingly, is higher among low-skilled workers than among middle- and high-skilled ones. All these differences may play a crucial role in career development, as it has been shown, for example in a study by van Eijck and De Graaf from 2004, that personality traits influence education attainment.

According to Judith Offerhaus’ paper from 2013, the more neurotic and agreeable individuals tend to be, the less likely they are to participate in lifelong learning. While neurotic individuals might avoid pursuing further training due to emotional instability, agreeable people may refrain from it to avoid any potentially arising disagreements. On the other hand, the more conscientious, extroverted and open-minded people are, the more often they tend to participate in lifelong learning. Conscientious individuals might have a high further training participation rate due to their well-structured work routine and persistent pursuit of long-term goals. Extroverted people may take up further training to increase their exchange with others and, since extroversion is a predictor for leadership positions, to prepare themselves for managerial responsibilities. Finally, openness to experience is associated with intellectual curiosity and willingness to learn new things.

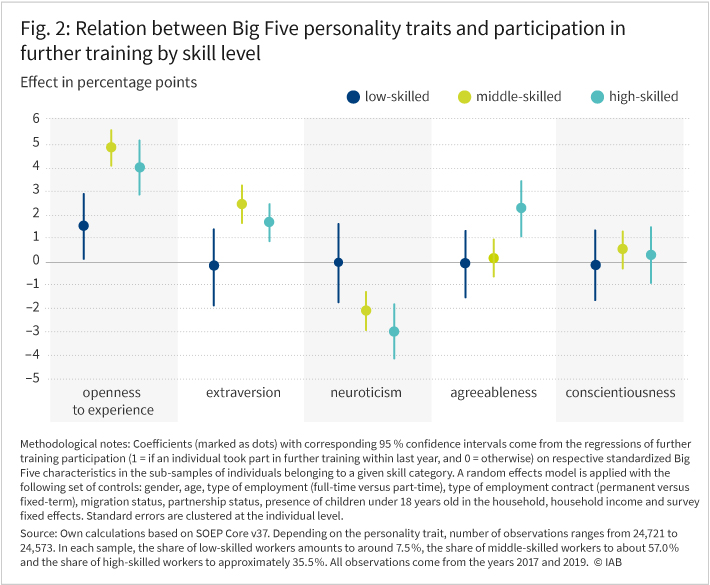

An evaluation of the relation between Big Five traits and further training participation within each skill group (see Figure 2) reveals that only openness to experience has a positive and statistically significant effect on all types of workers. However, this association is stronger for middle- and high-skilled adults than for low-skilled ones. In the former groups, a one standard deviation increase in openness to experience (which corresponds to a change by 1.03 points of the scale 1 to 7) relates to a 4-5 percentage points boost in the further training take-up probability within one year, while in the latter group it amounts only to a 1.5 percentage points increase. With respect to extroversion, the positive relation to further training participation is revealed only for middle-skilled (2.4 percentage points) and high-skilled (1.6 percentage points) workers. Here, one standard deviation translates to 1.14 points on the scale from 1 to 7. Similarly, the effect of neuroticism is pronounced only among more educated employees. One standard deviation increase in this personality traits (which corresponds to 1.23 points on the scale 1-7) is associated with respectively 2.1 and 3.0 percentage points decrease in the further training probability within one year for middle- and high-skilled workers. Further, the positive linkage between agreeableness and further training participation is limited only to high-skilled adults. Finally, contrary to the previously mentioned paper of Judith Offerhaus (2013), in this study conscientiousness does not relate to lifelong learning take-up for any of the skill groups.

To sum up, among all Big Five personality traits, openness to experience and extroversion positively relate to participation in further training within one year. While the former trait has an effect on all skill groups, the effect of the latter one is pronounced only among better-educated individuals. This means that motivating lifelong learning by referring to curiosity or imaginativeness might be a reasonable solution to increase participation among all workers, whilst relating to social aspects of training may trigger only middle- and high-skilled adults. In case of neuroticism, in contrast to other skill groups, the association with training participation among low-educated workers is negative but statistically insignificant. This finding suggests no evidence that, when it comes to low-skilled adults, being a more nervous, easily worried or stressed person result in a lower probability of undertaking extracurricular education.

Conclusion

The above analysis shows that while in the overall population of working individuals, personality traits such as LoC, openness to experience, extroversion, neuroticism and agreeableness relate to the probability of participation in further training, it is not necessarily the case within all skill groups. Among low-skilled individuals, only having an internal control belief and being an open-minded person are positively linked to take-up of lifelong learning. On the one hand, these results indicate the need for early investment in non-cognitive skills which positively relate to participation in lifelong learning. On the other hand, since different skill groups seem to be triggered for continued professional development in a different way, employers as well as employment agencies should pay attention to the structure of workers’ personality traits and skills while motivating further trainings. It would also be beneficial to assess which features of the training measure should be emphasised to motivate participation (e.g. broadening existing knowledge or improving professional networks). All in all, it seems that personality traits are not only an important indicator of educational attainment in early childhood, but are also crucial in later professional life in determining further training participation. Finally, to credibly evaluate the participation of differently skilled workers in further training activities, one has to also consider other personality traits (e.g. risk aversion, optimism), remaining participation obstacles such as institution and situation barriers, as well as the supply of training measures.

Data and Methods

The Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) is the largest and longest-running German panel study. Currently, around 30,000 respondents are interviewed each year. Among others, the SOEP provides information on training participation, personality traits and educational attainment.

In this study, both LoC and Big Five personality traits are defined as by Marie Laible et al. (2020) which results in age-free, standardised means across all waves for each individual in the data. In case of LoC, higher values indicate a more internal control belief.

Job-related lifelong learning is encoded using a question on the participation in education measures which were intended to deepen or expand existing professional qualifications, or to achieve a professional or academic credential within the last year. The training participation variable is then coded as 1 if an individual participated in further training within last year, and to 0 otherwise.

Finally, a skill-based distinction is made using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). According to it, low-skilled adults are these who reached a lower secondary education (ISCED 0-2), people in the middle-skilled group have an upper or post-secondary education (ISCED 3-4) and the group of high-skilled individuals constitute workers whose education is above the secondary educational level (ISCED 5-8).

Regarding the regression specification, a random effects model is used to consider unobserved individual characteristics, with the following set of controls: gender, age, type of employment (full-time vs. part-time), type of employment contract (permanent vs. fixed-term), migration status, partnership status, presence of children under 18 years old in the household, household income and survey fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the individual level.

Literature

Caliendo, M., D. A. Cobb-Clark, C. Obst, H. Seitz, and A. Uhlendorff (2022). Locus of Control and Investment in Training. Journal of Human Resources Vol. 57, No. 4, pp. 1311-1349.

Costa, P. T. and R. R. McCrae (1999). A Five-Factor Theory of Personality. In: John O. P., R. W. Robins, and L. A. Pervin, (Eds.) (2010): Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. New York: Guilford Press.

Fouarge D., T. Schils, and A. de Grip (2013). Why do Low-Educated Workers Invest Less in Further Training? Applied Economics Vol. 45, No. 18, pp. 2587-2601

Laible M.-C., S. Anger, and M. Baumann (2020). Personality Traits and Further Training. Frontiers in Psychology Vol. 11.

McCrae, R. R., and P. T. Costa (1994). The Stability of Personality: Observations and Evaluations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 3, No. 6, pp. 173–175.

Moutafi J., A. Furnham und L. Paltiel (2004). Why is Conscientiousness Negatively Correlated with Intelligence? Personality and Individual Differences Vol. 37, No. 5, pp. 1013-1022.

OECD (2019), Getting Skills Right: Engaging Low-Skilled Adults in Learning.

OECD (2021), Continuing Education and Training in Germany, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2023), Job Creation and Local Economic Development 2023: Bridging the Great Green Divide, OECD Publishing Paris.

Offerhaus J. (2013). The Type to Train? Impacts of Personality Characteristics on Further Training Participation. SOEPpapers, Vol. 531.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized Expectancies for Internal Versus External Control of Reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, Vol. 80, No. 1

Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), Data for Years 1984-2020, SOEP-Core v37, EU Edition, 2022.

Trahms, A., M.-C. Laible, and L. Braunschweig (2021). Geringqualifizierte bilden sich nach wie vor deutlich seltener weiter, IAB-Forum.

Van Eijck, C. J. M. and P. M. De Graaf (2004). The Big Five at School: The Impact of Personality on Educational Attainment. The Netherlands’ Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 4, No. 0(1), pp. 24-40.

In brief

- Low-skilled workers have less internal control belief than their more skilled counterparts, which means that they are more doubtful regarding their own influence on the events in their lives.

- Internal Locus of Control positively correlates with further training participation within all skill groups, although this association is stronger for more skilled individuals.

- Skill groups differ with respect to all Big Five characteristics; however, the greatest difference is visible in case of openness to experience, where low-skilled workers exhibit significantly lower values.

- Among Big Five characteristics, only openness to experience shows a positive and statistically significant relationship with further training participation among all types of workers. The strength of this association is stronger among more skilled individuals compared to less skilled ones.

- Only among more skilled workers, extraversion exhibits statistically significant and positive effects, while neuroticism shows a statistically significant and negative association with further training participation.

- Personality traits are not only an important indicator of educational attainment at younger age, but are also a crucial factor for further training participation later in life.

Picture: Gorodenkoff/stock.adobe.com

DOI: 10.48720/IAB.FOO.20241016

Galkiewicz, Agata Danuta; Kern, Jana (2024): Who is most open to lifelong learning? Exploring the role of personality traits and skills, In: IAB-Forum 16th of October 2024, https://iab-forum.de/en/https-www-iab-forum-de-en-url-titelform-who-is-most-open-to-lifelong-learning-exploring-the-role-of-personality-traits-and-skills/, Retrieved: 19th of February 2026

Diese Publikation ist unter folgender Creative-Commons-Lizenz veröffentlicht: Namensnennung – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de

Authors:

- Agata Danuta Galkiewicz

- Jana Kern

Agata Danuta Galkiewicz has been a member of the the team “Education, Training, and Employment Over the Life Course” of the IAB since January 2022.

Agata Danuta Galkiewicz has been a member of the the team “Education, Training, and Employment Over the Life Course” of the IAB since January 2022. Jana Kern is a research assistant in the RWI/IAB Junior Research Group “Ecological Transformation, Labour Market, Vocational Education and Further Training” at the Institute for Employment Research.

Jana Kern is a research assistant in the RWI/IAB Junior Research Group “Ecological Transformation, Labour Market, Vocational Education and Further Training” at the Institute for Employment Research.