15. January 2026 | Labour Market Policy

Minimum wage and job reallocation: The hidden role of financial constraints

In 2015, a nationwide minimum hourly wage of 8.50 Euro was introduced in Germany. Since then, research has consistently shown that the policy raised wages for low earners and reduced income inequality. As Christian Dustmann and colleagues demonstrated in a study from 2022, the effects on overall employment are limited. Instead, the reform led to reallocation of workers from less productive, lower-paying firms to more productive, higher-paying ones. However, not all firms were equally able to adjust to these changes. For instance, in a study from 2024, Hamzeh Arabzadeh and colleagues found that the decrease in wage inequality was much stronger for firms which faced difficulties in obtaining external financial resources. Since this brings further payroll pressure to the firm, it has important implications for how these firms adjust their workforce.

In this article, employment changes in firms before and after the minimum-wage introduction 2015 are analysed. Firms are separated into four groups according to their exposure to the minimum wage and to financial constraints (see Info box “Four categories of firms”):

- Minimum-wage unaffected, without financial constraints: minimum-wage bite below 5 percent and low leverage (leverage ratio below 50 %).

- Minimum-wage unaffected, with financial constraints: minimum-wage bite below 5 percent but high leverage (leverage ratio above 50 %).

- Minimum-wage affected, without financial constraints: minimum-wage bite above 15 percent and low leverage.

- Minimum-wage affected, with financial constraints: minimum-wage bite above 15 percent and high leverage.

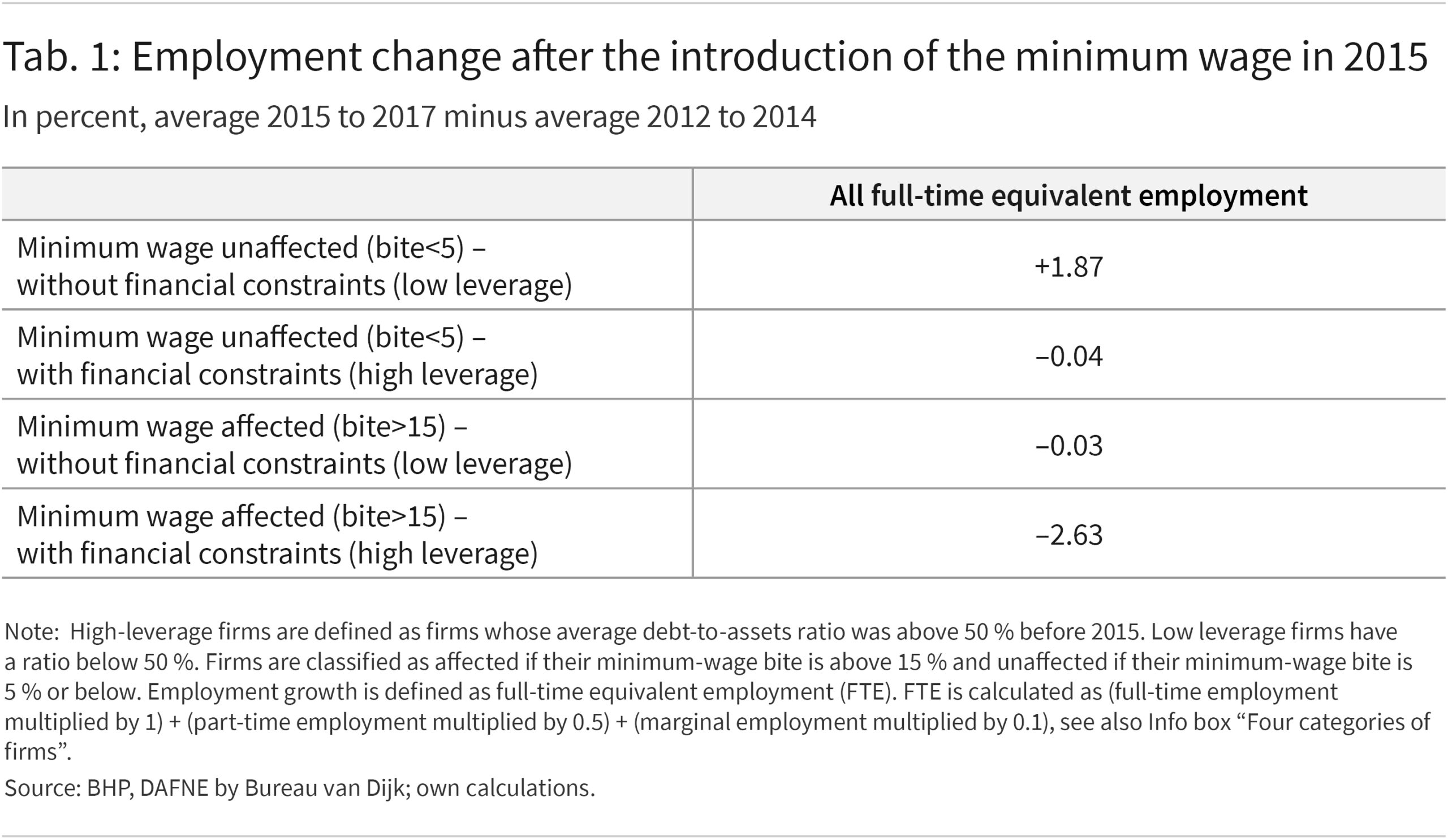

Employment growth after the introduction of the minimum wage is dependent on the firm’s financial constraints

When looking closer at the different categories of firms, a heterogeneous picture is revealed. The results show a clear pattern: financially unconstrained, unaffected firms — that is, those with strong balance sheets and limited exposure to the minimum wage — experienced the strongest employment growth after the minimum wage was introduced. By contrast, employment declined strongly in firms which were minimum wage affected and financially constrained. Table 1 illustrates employment growth for all four groups, based on full-time equivalent (FTE) employment—a measure that captures total labour input across different contract types :

The employment in firms with low debt ratios and low minimum wage bite (minimum wage unaffected, without financial constraints firms) increased almost by 2 percent after the introduction of the minimum wage. This is the only group that experienced employment growth, which suggests that employment reallocated to these firms after the introduction of minimum wage. Employment in firms with low minimum wage bite but high financial constraints, or firms with no financial constraints but high minimum wage bite stayed the same. The sharper contrast appears when taking financially constrained firms into account: Employment stayed the same for those firms that were unaffected by the minimum wage with financial constraints. This underscores that financial constraints limit firms’ growth capacity. Finally, for the firms which were affected by the minimum wage, and which were financially constrained, employment strongly declined by 2.6 percent. The combination of higher payroll expenses due to the introduction of minimum wage and financial constraints exert an additional limit on firms’ growth capacity which brought this strong decline in employment. One concern is that financial constraints are related to a firm’s size, growth potential and productivity, which in turn may affect how the minimum wage can be absorbed by the firm.

However, an analysis by Almut Balleer and others (2025) that controls for firm observables including size, growth and productivity before the introduction of minimum wage reveals that the effects of financial constraints on employment remain strong. These results suggest that while the introduction of the minimum wage may not have caused large changes in total employment, it nevertheless created strong reallocation effects. Financial flexibility plays a crucial role in enabling firms to adapt to wage increases without cutting jobs.

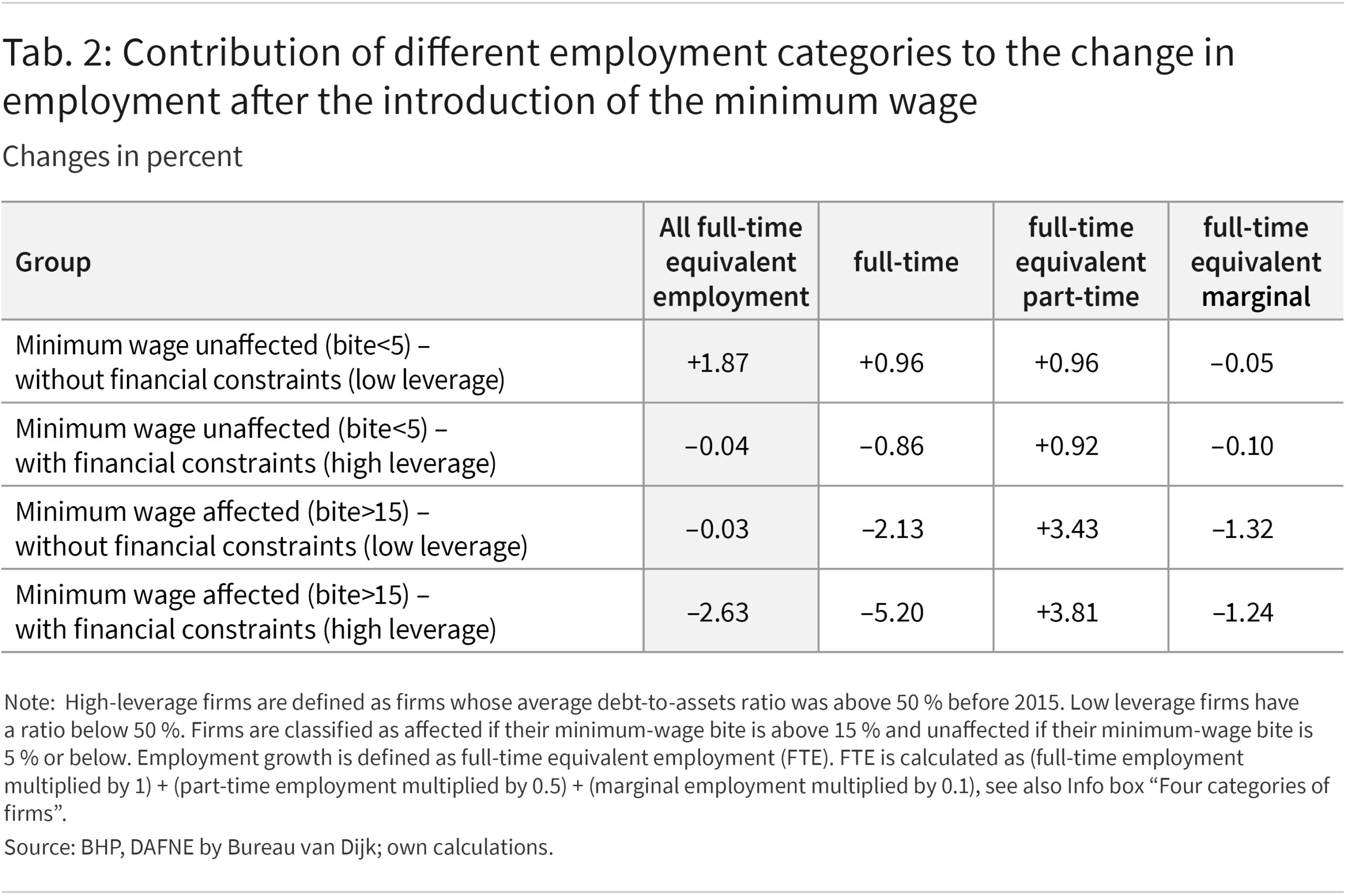

Looking deeper: Where does the employment change come from?

Table 2 shows how different employment types contributed to the change in total full-time equivalent employment for each group. Interestingly, full-time employment only increased in financially unconstrained firms that were not affected by the minimum wage. Here, employment gains are evident for both full-time and part-time employment. In contrast, total full-time employment declined by 0.9 percent in minimum wage unaffected but financially constrained firms. This decline is, however, compensated by a similar increase in part-time employment.

In minimum wage affected but financially unconstrained firms, full-time employment declined as well, but there was strong employment growth as an increase in part-time employment more than compensates for this decline. This suggests that firms respond to higher wage-costs by reallocating labour from full-time to part-time rather than reducing overall employment. Moreover, the minimum wage caused a strong decline in marginal employment for affected firms. Part of the movement from marginal to part-time employment may be mechanical as some workers move above the mini-job limit due to the minimum wage. The decline of full-time employment in affected and financially constrained firms is strikingly high: it decreased by 5.2 percent relative to total employment, and part-time gains were not enough to offset these losses.

These findings suggest that the minimum wage exerts moderate losses in full-time employment, but increases part-time employment and drives a decline in marginal employment. Financial constraints strongly reinforce this pattern for full-time employment, whereas the effects of the minimum wage are similar for part-time and marginal employment, irrespective of whether the firm is financially constrained or not. This finding is in line with the interpretation that financial constraints incline firms to cut costs for more expensive employees, i.e. full-time workers. Financial constraints result in a reallocation of full-time employees from affected-constrained firms to unaffected-unconstrained firms.

Conclusion

The German minimum wage raised wages without reducing aggregate employment, but not all firms responded equally. Financially constrained firms – especially those strongly affected by the minimum wage – reduced employment, particularly amongst full-time workers. Financially unconstrained firms were more resilient, often growing even in the face of wage increases. This highlights the role which access to financial resources plays when firms adjust to wage policy changes without cutting jobs.

Four categories of firms based on minimum wage exposure and financial constraints

-

“Minimum wage bite”: Firms’ exposure to the minimum wage

Minimum wage bite is defined as the extent to which a firm’s wage structure is impacted by the need to raise wages to meet the new minimum wage. A high minimum wage bite indicates that a firm faces a significant increase in personnel costs. This is typically the case when a large proportion of employees previously earned below the minimum wage or when their wages were far below the new threshold. Firms with a bite above 15 percent are considered affected, while those with a bite below 5 percent are classified as unaffected.

-

Firms’ financial constraints: financial leverage

Financial constraints are restrictions on a firm’s ability to access external financial resources that may be used to invest, hire, or adjust wages in response to external or internal changes. Financial constraints are measured using leverage, calculated as the ratio of a firm’s total debt (current and long-term liabilities) to its total assets. For example, a leverage ratio of 50 percent means a firm’s total debt equals half of its assets, with higher ratios indicating greater reliance on external financing. In the data used here, around 30 percent of firms had leverage ratios above 50 percent before the minimum wage introduction. This is the threshold used here to classify firms as financially constrained. The idea is that potential lenders will be more reluctant to lend, will ask for higher interest, or higher collateral in order to grant additional finance to a firm which is already highly indebted. For example, Xavier Giroud and Holger M. Mueller demonstrated in 2017 that highly leveraged firms are less able to raise additional debt and consequently experienced larger employment losses during the financial crisis of 2008.

Four categories of firms:

-

- Minimum wage unaffected, without financial constraints firms are those firms that have a minimum wage bite below 5 percent, meaning that they needed to increase their payroll by less than 5 percent due to the introduction of minimum wage. And for whom financial constraints were not binding as their leverage ratio is below 50 per cent.

- Minimum wage unaffected, with financial constraints firms are those firms with low minimum wage bite as above and firms with leverage ratio above 50 per cent.

- Minimum wage affected, without financial constraints firms are those firms that have a minimum wage bite above 15 percent and firms with low leverage.

- Minimum wage affected, with financial constraints firms are those firms that have a minimum wage bite above 15 percent and firms with high leverage.

-

Full-time equivalent employment

The employment structure — in terms of full-time, part-time and marginal employment shares — is very different across the firms analysed. To be able to compare employment across firms with different workforce structures, part-time and marginal employment shares have been converted to full-time equivalents. This makes it possible to aggregate different types of employment into a unified measure of labour input at the firm level.

We convert part-time employment and marginal employment to full-time equivalent employment as follows:

-

- Full-time employment counts as 1

- Part-time employment counts as 0.5

- Marginal employment counts as 0.1

Example:

If a firm has 10 full-time, 10 part-time and 10 marginal employees, its full-time employment is: 10 (full-time)+ 10 x 0.5 (part-time) + 10 x 0.1 (marginal) = 16 full-time equivalent employment.

In brief

- The introduction of Germany’s minimum wage in 2015 did not cause substantial changes to total employment but triggered large shifts in the composition and allocation of types of employment.

- Financially unconstrained firms not affected by the minimum wage experienced an increase in employment both for full time and part-time work.

- Firms affected by the minimum wage moved away from full-time to part-time employment after the introduction of minimum wage.

- Financially constrained firms (especially those which were exposed to the minimum wage policy) experienced (sizeable) losses in full-time employment.

- The results indicate that minimum-wage policy reinforced a reallocation of workers away from financially constrained firms.

Literature

Arabzadeh, Hamzeh; Balleer, Almut.; Gehrke, Britta; Taskin, Ahmet Ali (2024): Minimum wages, wage dispersion and financial constraints in firms. European Economic Review, No. 163, Art. 104678.

Balleer, Almut; Gehrke, Britta; Taskin, Ahmet Ali (2025). Mindestlohn als Stresstest: Finanzielle Spielräume. Wirtschaftsdienst, Vol. 105, No. 10/2025, pp. 758-762.

Bossler, Mario; Schank, Thorsten (2023): Wage inequality in Germany after the minimum wage introduction. Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 41, No. 3/2023, pp. 813-857.

Dustmann, Christian; Lindner, Attila; Schönberg, Uta; Umkehrer, Matthias; vom Berge, Philipp (2022): Reallocation effects of the minimum wage. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 137, No. 1, pp. 267-328.

Giroud, Xavier; Mueller, Holger M. (2017): Firm leverage, consumer demand, and employment losses during the great recession. The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 132, No. 1/2017, pp. 271-316.

picture: Andreas Karelias / stock.adobe.com

doi: 10.48720/IAB.FOO.20260115.02

Taskin, Ahmet Ali; Gehrke, Britta (2026): Minimum wage and job reallocation: The hidden role of financial constraints, In: IAB-Forum 15th of January 2026, https://iab-forum.de/en/minimum-wage-and-job-reallocation-the-hidden-role-of-financial-constraints/, Retrieved: 13th of March 2026

Diese Publikation ist unter folgender Creative-Commons-Lizenz veröffentlicht: Namensnennung – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de

Authors:

- Ahmet Ali Taskin

- Britta Gehrke

Ahmet Ali Taskin, Ph. D., is a senior researcher in the Forecasts and Macroeconomic Analyses (MAKRO) research area at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB).

Ahmet Ali Taskin, Ph. D., is a senior researcher in the Forecasts and Macroeconomic Analyses (MAKRO) research area at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). Prof Dr Britta Gehrke has been Professor of Macroeconomics at Freie Universität Berlin since April 2023.

Prof Dr Britta Gehrke has been Professor of Macroeconomics at Freie Universität Berlin since April 2023.