16. September 2024 | Groups of Persons

Female university students may settle for considerably lower starting salaries than their male peers

According to the German Federal Statistical Office, women earn on average 18 percent less than men. In principle, many different factors are responsible for this gender pay gap. However, even when important structural factors are considered and only employees with the same position, qualifications and occupation are compared, women still earn an average of 6 percent less than their male counterparts. This shows that the continuing pay gap between women and men is an obstacle to real social and economic equality between these two genders in Germany.

Closing the gender pay gap is an important concern of policymakers. In the public debate on gender inequality, however, too little attention is paid to the fact that gender differences in expected wages may arise already before entering the labour market. Such differences not only reflect the actual pay gap between women and men but also contribute to it through their influence on later earnings opportunities.

Most people make decisions about their career long before they actually start their first job. These decisions can have far-reaching and long-term consequences for their professional future, which may depend, for example, on the salary expectations young people have before entering the labour market. For instance, someone who is satisfied with a lower starting salary in return for greater flexibility in the job may make different career choices from someone who accepts less favourable working conditions for a higher starting salary. What’s more, a gender pay gap at the start of a career could persist or even increase over the course of a working life.

Women have lower wage expectations and settle for lower starting salaries than men

It has often been pointed out in the economic literature that women and men have very different wage expectations even before their first job after graduation. A survey conducted in December 2020 as a part of the BerinA study (“Career entry of university graduates”) confirms these findings. In the survey, university students were asked about their wage expectations at the end of their master’s degree. First, they were asked to indicate their so-called reservation wage, i.e. the minimum monthly wage they are willing to accept for their first job after graduation.

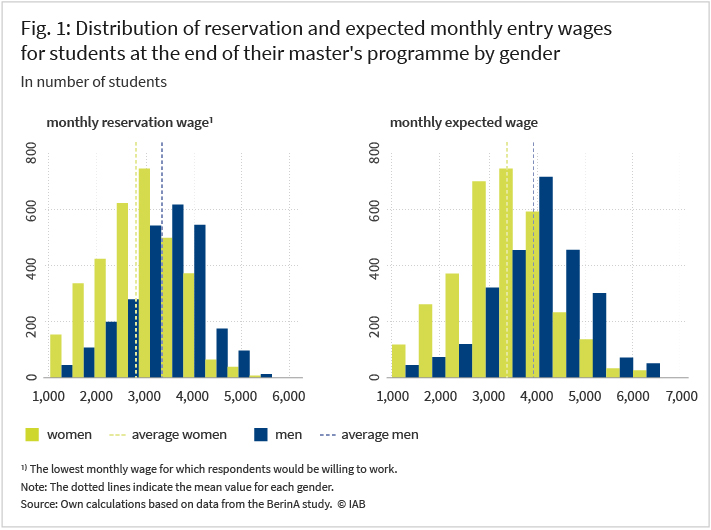

They were then asked what monthly wage they expect to earn in their first job. Figure 1 shows that even before entering the labour market, women and men have very different salary expectations.

On average, female students would accept a monthly starting salary that is 523.28 euros, or 15.6 percent, lower than that of their male counterparts. The expected monthly salary, which is considerably higher, also shows a gender gap of 585.51 euros, or 14.7 percent. Thus, even shortly before graduation, women perceive their labour market value to be significantly lower than men.

There are several reasons for gender differences in wage expectations

The reasons for these gender differences can be determined with the help of a so-called decomposition analysis. It shows which components contribute to the explanation of the gender differences and to what extent.

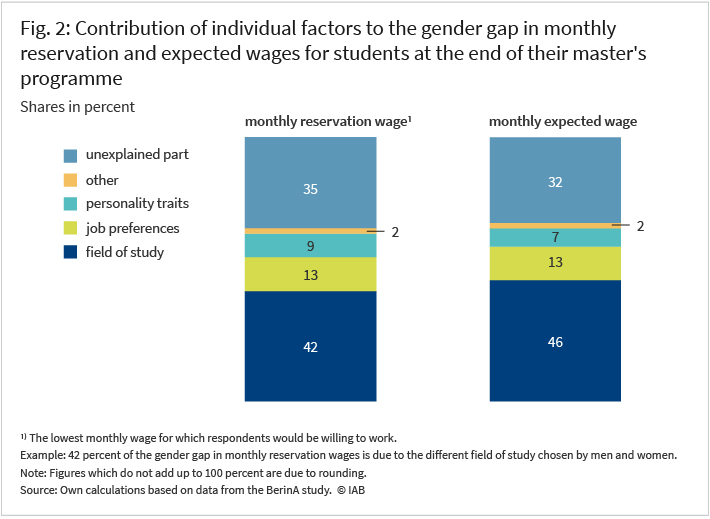

As Figure 2 shows, three main mechanisms contribute to explaining the gender gap in wage expectations: differences in subject choice, different career preferences and a set of personality traits that differ by gender. These mechanisms are analysed in more detail below.

The ‘unexplained’ part, on the other hand, includes influencing variables that cannot be observed in the available data. These include gender-specific information gaps, e.g. on the level of salaries in certain segments of the labour market, and some unobserved differences between men and women that lead to the gender pay gap.

Field of study explains a significant part of the observed differences in wage expectations

Students in different fields of study have different earnings prospects after graduation. In male-dominated fields of study, starting salaries after graduation are typically higher than in fields of study with a higher proportion of women. It can therefore be assumed that the choice of the field of study explains a large part of the differences in salary expectations between female and male students. For example, humanities subjects remain more popular among women and generally offer lower employment and earnings prospects than many STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects, which tend to be chosen by men.

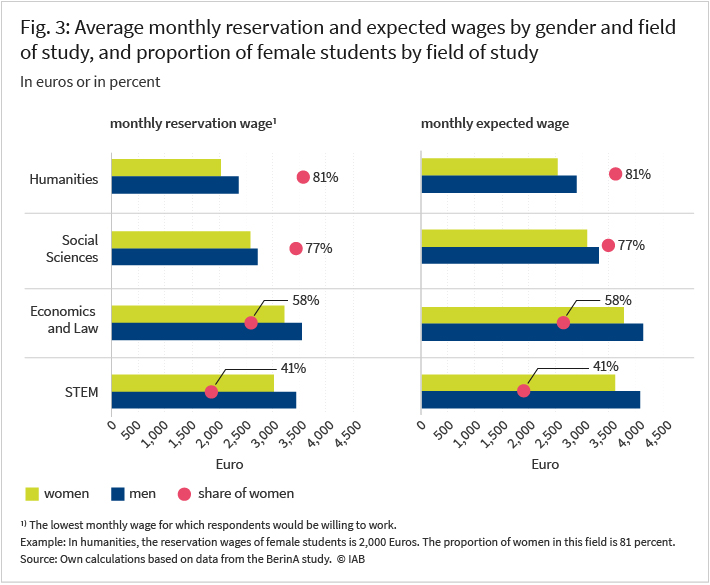

As Figure 3 shows, women are about four times more likely (share of roughly 80 percent) to choose subjects in the humanities and social sciences, where wage expectations are much lower than in STEM subjects or in economics and law – by a total of up to 1,200 euros per month. The importance of the field of study in explaining the gap in salary expectations (see Figure 2) is therefore mainly due to the fact that women are much more likely than men to choose fields of study that are comparatively less well paid in later working life.

However, subject choice is not the only reason for the observed differences. Within each of the four subject groups, male students reported reservations and expected salaries that were still between 5.7 and 14.6 percent higher than those of their female counterparts. These differences are particularly large for students in the humanities (14.6 percent vs. 11.7 percent) and smallest in the social sciences (5.7 percent vs. 6.4 percent).

Although differences in the field of study explain a large part of the differences in wage expectations, women systematically rate their value on the labour market lower than their male counterparts, even when they have chosen the same field of study.

Women and men have different career preferences

Gender differences in career preferences also contribute significantly to differences in observed wage expectations. This can be shown both for the preferred sector of employment, i.e. the public or the private sector, and the preferred weekly working hours, as well as for a range of other criteria that are important to women and men when deciding on a particular job. Along all three dimensions, the preferences of women and men differ significantly.

On the one hand, men are more likely than women to pursue employment in the private sector. While almost half of all male students (48.0 percent) indicated that they were looking for a job exclusively in the private sector, this was the case for less than one third of their female peers (32.1 percent). In contrast, women prefer to work in the public sector (16.9 percent versus 11.6 percent) or are equally open to both sectors more often than men (42.9 percent versus 36.0 percent).

This can be seen as evidence that women often prefer to be employed in the public rather than the private sector compared to men, which they may perceive as being more secure. As public sector wages are lower on average, women may be more willing than men to accept lower pay in return.

On the other hand, female respondents on average prefer to work fewer hours per week than their male counterparts. While more than one in three male graduates (34.9 percent) would be prepared to work more than 40 hours per week, this is the case for less than one in four female graduates (23.4 percent). Women were also almost twice as likely to say that they would like to start their career with a part-time job (6.5 percent compared to 3.6 percent), which tends to be lower paid on average.

Finally, there were significant differences in the criteria that women and men considered important when looking for a job. Compared to women, men are more likely to consider income and career-related criteria such as ‘salary offered’ (46.3 percent versus 37.4 percent) or ‘good career opportunities’ (28.0 percent versus 18.0 percent) as very important. On the other hand, non-monetary selection criteria tend to be more important for women than for men when looking for a job. This applies, for example, to ‘good working conditions’ (26.5 percent versus 18.7 percent) or ‘pleasant working atmosphere’ (29.3 percent versus 20.9 percent). Thus, women are more likely to choose jobs with non-financial amenities and lower pay, while men choose higher-paid, career-oriented jobs.

Personality traits that are on average more pronounced in men are often associated with higher wage expectations

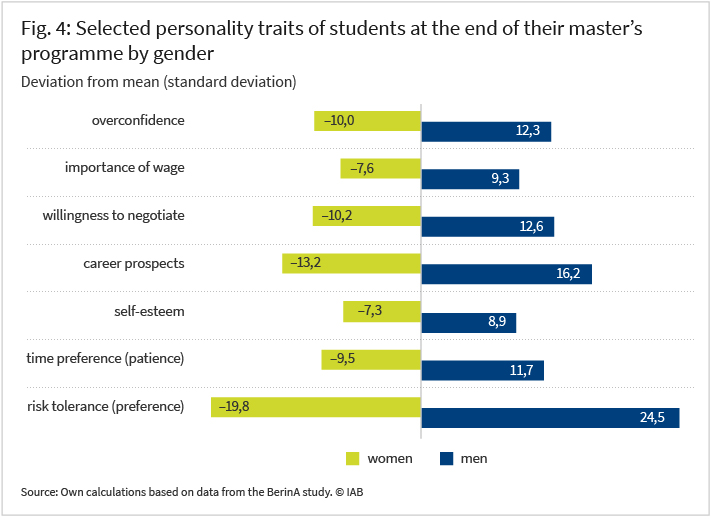

Personality traits play an important role in explaining the gender pay gaps. As Matthias Collischon has shown in an article published in 2022 for the IAB Forum, personality traits have an impact on the gender pay gap. This is also confirmed by the analysis of the BerinA survey, which collected information on six different personality traits that are potentially relevant for explaining gender differences in reservation wages and expected wages (see Figure 4). As Figure 2 shows that the personality traits can explain between 7 and 9 percent of the differences in graduates’ reservation and expected wages.

The results show that male respondents scored higher than their female counterparts on every single trait measured. On average, men stated that they were more willing to take risks and were more patient, had greater self-confidence and better career prospects. In addition, they were more likely to negotiate their salary with their employer. Furthermore, they were more likely than women to overestimate their academic achievements. The gender difference is strongest for respondents’ risk preference and weakest for their self-confidence.

The analysis also shows that for four of these six characteristics, a higher level is associated with a higher perceived earning potential. Only for two dimensions is this not the case: students who rate themselves as having above-average patience or who overestimate their academic performance do not, on average, report higher reservation salaries or salary expectations.

Overall, personality traits could therefore be another reason why female students would expect or accept significantly lower salaries than their fellow students. According to their own statements, they are on average less willing to take risks, have less self-confidence, rate their career prospects as worse and are less willing to negotiate their salary than men.

Conclusion

While many political interventions usually target existing gender pay gaps, the aim should be to counteract the emergence of such gaps in the first place. It is certainly helpful to encourage girls and young women to be more open to better-paid – and typically male-dominated – occupations. However, the results presented here suggest that this alone will not be enough to eliminate the observed gender gaps in wage expectations.

It is therefore important to strengthen the personality traits of girls and young women that – at least statistically – promise greater success in the labour market. For example, many previous studies suggest that the pay gap between women and men is partly due to differences in their negotiating behaviour. As men are generally more confident and willing to take risks, they negotiate their salaries with potential employers more often and more successfully than women. Seminars and workshops, for example negotiation training, specifically aimed at women, could help to improve women’s negotiation success.

Despite various explanatory factors, an important part of the observed gender gap remains unexplained, suggesting that these differences are partly due to gender differences in unobserved characteristics. For example, women may be systematically less informed about their earnings opportunities after graduation than men. Thus, it should be investigated to what extent existing information channels on occupation-specific career and earnings opportunities can be improved.

Students should be as well informed as possible about what they can expect in the labour market after their studies, regardless of their gender. For example, comprehensive information campaigns targeted at young women in schools and universities could help to reduce the gender pay gap when they enter the labour market. Such measures could help in decreasing the gender gap in wage expectations. In addition, programmes that specifically bring together female pupils and students with representatives from traditionally male-dominated industries and occupations could help to attract women to occupations that tend to be better paid and in which they might not otherwise be interested.

Lower wage expectations can mean that women do not enter into wage negotiations as often as men, or when they do, they negotiate for lower wages than men. This in turn can widen the gender pay gap. Policymakers should therefore also try to focus on factors that indirectly contribute to women receiving lower starting salaries on average than men. For example, greater wage transparency could help women to align their wage expectations with those of men in the same or similar occupations, thus giving them a more favourable starting position in wage negotiations.

A first step in this direction was the enactment of the ‘Pay Transparency Act’ in 2017 although a corresponding evaluation has shown that its effectiveness has so far been limited. Further measures are therefore needed to improve pay transparency at all levels, particularly in institutions that are not already covered by existing statutory regulations.

Fixed salary components could also help to counteract the role of individual wage negotiations and, indirectly, the gender wage gap. According to a study published in 2020 by the Hans Böckler Foundation’s Institute for Economic and Social Research, only around half of all employees in Germany are covered by collective bargaining agreements – and the trend is downwards. Expanding the range of collectively agreed upon wages or pay components by providing firms with appropriate incentives could be helpful. Whether such measures can effectively reduce gender inequality, however, can only be clarified by further research.

In brief

- There is still a pay gap between women and men. This is probably due, at least in part, to gender differences in wage expectations before entering the labour market.

- Female university students, on average, expect a starting wage around 15 percent lower than their male peers. They are also willing to accept a job with a lower starting wage.

- There are several reasons for the gender gap in wage expectations. Women are more likely to choose subjects that tend to pay less later on, and to choose more secure but lower paid jobs. They are also less willing to take risks and have less self-confidence than male students.

- However, these factors do not explain the entire gap in wage expectations. The unexplained part of around 32 percent could be due to information gaps or other unobserved factors.

- In any case, policy measures are needed to support female students entering the labour market and to address the emergence of gender pay gaps at an early stage.

Picture: Tomertu/stock.adobe.com

DOI: 10.48720/IAB.FOO.20240916.02

Setzepfand, Paul; Yükselen , Ipek (2024): Female university students may settle for considerably lower starting salaries than their male peers, In: IAB-Forum 16th of September 2024, https://iab-forum.de/en/female-university-students-may-settle-for-considerably-lower-starting-salaries-than-their-male-peers/, Retrieved: 25th of February 2026

Diese Publikation ist unter folgender Creative-Commons-Lizenz veröffentlicht: Namensnennung – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de

Authors:

- Paul Setzepfand

- Ipek Yükselen

Paul Setzepfand completed an internship in the research area “Education,Qualification and Employment Trajectories” at the IAB from March to May 2022.

Paul Setzepfand completed an internship in the research area “Education,Qualification and Employment Trajectories” at the IAB from March to May 2022. Ipek Yükselen is a researcher in the department "Education, Training, and Employment over the Life Course" at the IAB.

Ipek Yükselen is a researcher in the department "Education, Training, and Employment over the Life Course" at the IAB.