9. July 2024 | Forms of Employment

Gig-work in the German delivery-services sector: Employment has increased significantly in recent years

Martin Friedrich , Ines Helm , Ramona Jost , Julia Lang , Christoph Müller

With the rise of app-based delivery services, a robust discussion has arisen in the media about the working conditions of the drivers they employ. The phenomenon is part of the wider trend of organising work through digital platforms. Work on and with such platforms is characterised by the placement of mostly small or time-limited work assignments via apps or websites. A distinction is made between location-independent and location-based digital platform work. In this article, only services which are carried out on-site are considered. These services are also referred to as gig-work (see the explanations in the info box “Digital platform work”).

Digital work platforms place orders with solo self-employed people, or they employ people to provide services. In Germany, digital work platforms have moved to employing platform workers on a dependant basis due to the institutional framework, which, amongst other things, foresees harsh consequences for false self-employment, as Corinna Funke and George Picot explain in their study published in 2021.

As part of a research project funded by the think tank “Digital, Work and Society” of the German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, a database was created for the first time to examine the phenomenon of gig-work in Germany in detail. For this purpose, administrative data from the IAB was used, which is based on employers’ social-security reports (for more information see the info box “Data”). The data includes all dependant employees of the major companies in the gig-economy. This article focuses on app-based delivery services as the most prominent form of gig-work and asks: How has dependant employment in these delivery services developed in Germany; what aspects characterise this form of employment; and how do gig-workers compare with employees in low-skilled jobs?

Gig-work grew particularly rapidly during the Covid-19 pandemic

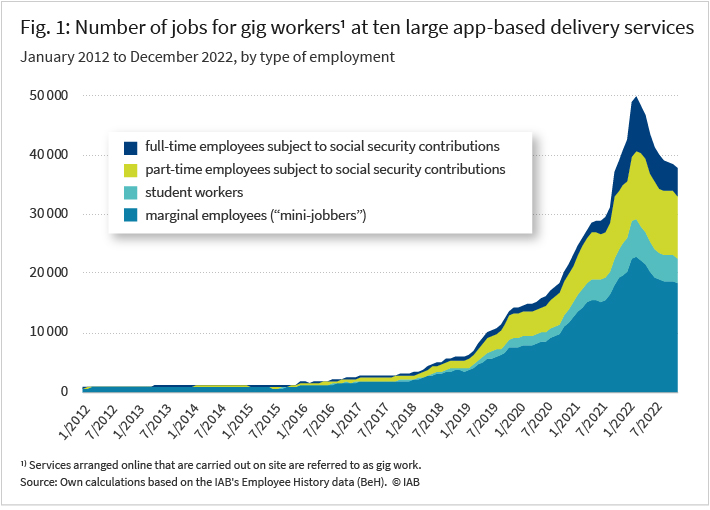

Gig-work in app-based delivery services is a comparatively recent phenomenon in Germany. Figure 1 uses monthly data from ten large companies to show the development of dependant employment in this sector between 2012 and 2022: Whilst the number of jobs was still negligible in 2012, strong growth set in over time, especially from 2018 onwards. During the Covid-19 pandemic, employment reached its peak with up to around 50,000 jobs.

This is consistent with the findings of a contribution to the IAB Forum from 2020 by Anja Bauer and colleagues, which points to increased demand for delivery services in the wake of contact restrictions and lockdowns.

Even though the total number of gig-jobs in delivery services is relatively moderate, the phenomenon still affects many people. During 2022, a total of around 94,000 people worked as gig-workers for a delivery service at least once throughout the year. This indicates that the employment relationships are often short-term and that existing jobs are constantly being filled by new recruits (see table).

Figure 1 also shows the composition of gig-workers by type of employment: In 2021 and 2022, almost half of all gig-workers were marginally employed and 12 percent were student-workers. However, an increasing proportion of gig-work is carried out in part-time and full-time employment subject to social security contributions: 27 percent of gig-workers were employed part-time, 12 percent worked full-time (see Figure 2).

Typical gig-workers in delivery services are young, male and have a foreign nationality

In view of the increasing ⎼ albeit, compared to other labour market segments, relatively low proportion of employment subject to social insurance contributions ⎼ the question now arises as to which groups of people pursue this form of work, the level of income earned, and what consequences this has for the social security of employees.

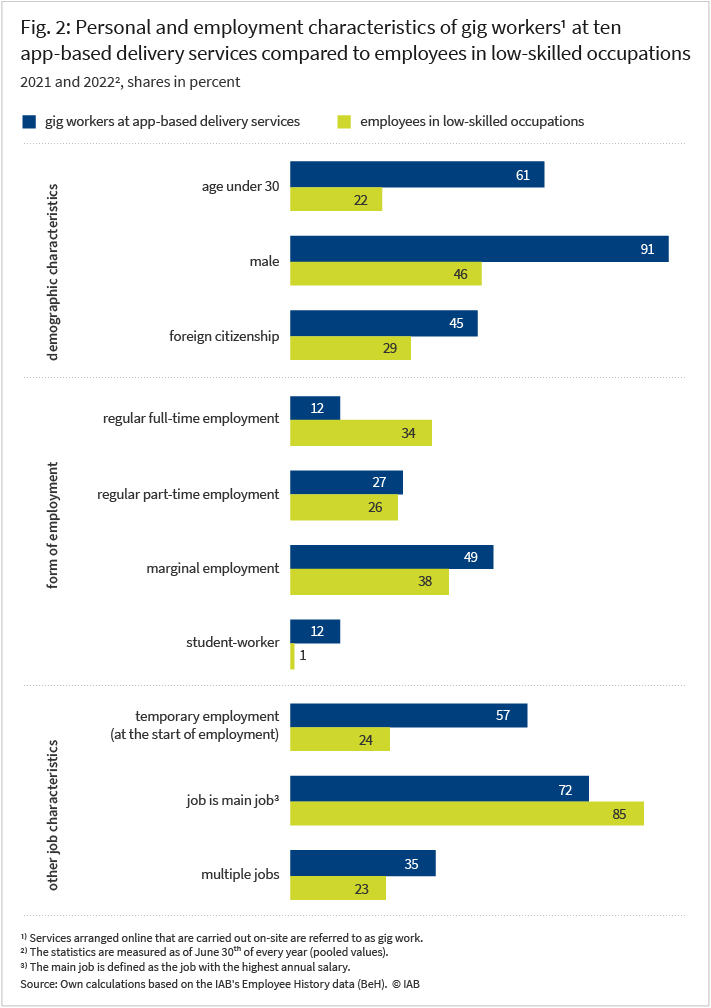

Figure 2 first compares various personal characteristics of gig-workers in delivery services with those of workers in low-skilled jobs more widely, for the years 2021 and 2022. As a rule, no specific specialist knowledge is required to carry out low-skilled jobs and, similar to gig-work, they offer low-threshold access to work.

The comparison shows: 61 percent of gig-workers are younger than 30 years, compared to 22 percent in the comparison group. 91 percent of gig-workers in app-based delivery services are men. This proportion is therefore almost twice as high as the number of workers in low-skilled occupations overall. The findings on age and gender are consistent with a current US-study by Andrew Garin and others from 2023.

Gig-workers are also more likely to have foreign citizenship. The majority of foreign gig-workers come from countries in South Asia (31 %), West and Central Asia (20 %) and Eastern Europe (15 %). The foreign employees in the comparison group, on the other hand, most often come from countries in Eastern Europe (33 %), Southern Europe (25 %) and West and Central Asia (21 %).

Compared to employees in low-skilled occupations, gig-workers are less likely to be in regular full-time employment and are more likely to be in part-time employment or to be student-workers. At the beginning of the employment, the employment relationship is also more often temporary and the job is less often the main occupation. 35 percent of gig-workers carry out more than one job at the same time, whereas this applies to 23 percent of employees in the comparison group.

Gig-work in delivery services is usually short-term and low-paid

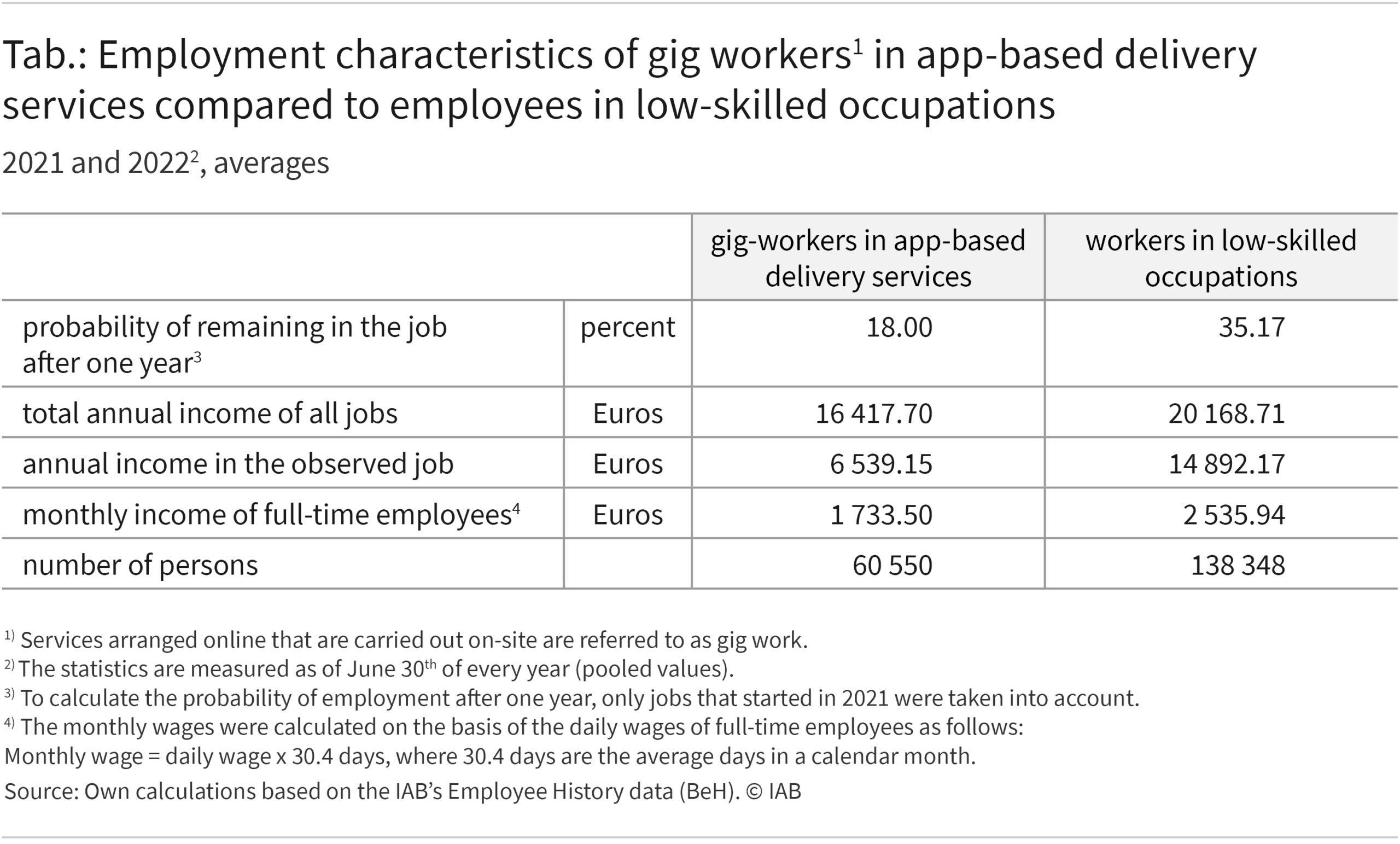

If you compare the length of employment and income of gig-workers in delivery services with those in low-skilled jobs more generally, there are clear differences (see Table 1). Whilst a good third of the people in the comparison group are still working in the same job one year after starting the job in 2021, the figure for gig-workers is only 18 percent.

The incomes of gig-workers and employees in the comparison group are shown for employment relationships in 2021 and 2022: Whilst gig-workers earn an average an annual income of around 6,500 euros from their work at a single delivery service, the annual income of employees in low-skilled jobs is around 14,900 euros. If you add up the annual income from all of a person’s jobs, the difference between the two groups becomes smaller, because gig-workers are more likely to have multiple jobs at the same time.

For full-time employees in platform-work there is also a clear difference in the monthly gross income between the two groups: gig-workers earn an average of just over 1,700 euros, which is around 800 euros less than full-time employees in low-skilled jobs generally.

Conclusion

Employment in app-based delivery services has increased significantly in recent years and reached its peak during the Covid-19 pandemic. Gig-workers in the delivery-services sector are predominantly male, comparatively young and often do not have German citizenship.

From an individual perspective, employment in delivery services can be precarious: First of all, even when the job is full-time, the income is relatively low. Furthermore, 61 percent of gig-workers are marginally employed or are hired under working student contracts. These gig workers pay no contributions to the unemployment insurance and are hence not covered. Also, they pay no or only limited pension-insurance contributions, which may lead to financial disadvantages in old age.

However, gig-work could help marginalised groups in particular to enter the labour market and act as a stepping stone to more stable employment. This question, alongside other aspects, will be examined in the further course of the project.

References

Fairwork (2022): Fairwork Germany Ratings 2021: Labour Standards in the Platform Economy. Berlin, Oxford.

Funke, Corinna; Picot, Georg (2021): Platform work in a coordinated market economy. In: Industrial Relations, Vol. 52, pp. 348–363.

Garin, Andrew; Jackson, Emilie; Koustas, Dmitri K.; Miller, Alicia (2023): The Evolution of Platform Gig Work, 2012-2021. In: National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No w31273.

OECD/ILO/European Union (2023): Handbook on Measuring Digital Platform Employment and Work. OECD Publishing.

Digital platform work

According to a 2023 definition by OECD, ILO and Eurostat, employment on a digital platform includes all activities carried out by a person through or on a digital platform, with the intention of obtaining remuneration or profit. In addition, essential aspects of the activities must be controlled and/or organised through the digital platform (usually via a smartphone app), such as access to customers, the evaluation of the activities carried out, the tools required to carry out the work, the facilitation of payments, and the distribution and prioritisation of the work to be carried out. In addition, the work must last at least one hour within a given a reference period.

A distinction can be made between location-independent platform work (cloud work such as freelance programming, microtasking) and location-based platform work (gig-work, e.g. driver services, delivery services). The IAB project, of which this paper forms a part, examines gig-workers, i.e. employees of location-based platforms. This also includes delivery services.

Gig-work means that digital work platforms place jobs with solo self-employed people or employ people directly to provide services. App-based delivery services in Germany employ a significant number of gig-workers, such as drivers (“riders”) or warehouse workers (“pickers”).

Data

The basis for identifying dependant employees in gig-economy companies is the IAB’s employee history (Beschäftigungshistorik, BeH), whose data is based on employers’ (annual) reports to the social security institutions. This data contains information on the start- and end-dates of all reported employment in Germany as well as earnings. In addition, numerous statistical characteristics of jobs and individuals are made available for research purposes.

The IAB’s administrative data can be linked to address data from the Federal Employment Agency (BA) for selected research projects. In this project, the address data of the companies is used to identify known digital work-platforms with their associated establishments and to link the data of all employees there. To identify relevant digital work-platforms in Germany, findings from Fairwork’s studies on gig-work in 2022 as well as our own evaluation of app charts were used.

For the analyses presented here, the data is limited to ten major delivery-service providers that had 49,320 employees as of the 30 June 2022, 88 percent of whom were gig-workers. The latter are identified using the following occupational descriptions (codes), which indicate gig-work and often occur within those companies: warehouse assistants, postal and delivery assistants and road-transport workers, sales workers and catering workers. The analyses here relate exclusively to employees in these professions. The remaining 6,026 employees (12 %) of the ten app-based delivery services examined often work in highly qualified professions such as software developer, business economist or logistics manager.

A sample of employees in low-skilled jobs from cities in which gig-workers are also providing delivery services provides a comparison group. For this purpose, a 2 percent sample of the BeH data was used and in this sample all people who were registered as employed in a low-skilled occupation on the 30 June 2021 or 2022 respectively, were selected.

Low-skilled occupations have the comparatively lowest level of requirements and include occupations with simple, less complex (routine) activities, for which as a rule little or no specific specialist knowledge is required and for which entry is therefore low-threshold. Due to the low complexity of the activities, usually no formal vocational qualification is required or only one year of (regulated) vocational training. Employees in low-skilled occupations are therefore suitable as a comparison group, as delivery-service jobs have similar entry conditions.

Because app-based delivery services practically only employ gig-workers in larger cities, people who work in (mostly rural) regions where there are no significant numbers of gig-workers were excluded from the comparison group.

In brief

- A new dataset from the IAB makes it possible for the first time to examine the situation of dependant employees of major gig-economy companies in more detail. The majority of these companies are app-based delivery services.

- Dependant employment at platform companies offering delivery services has risen sharply in recent years and reached its peak during the Covid-19 pandemic. Almost half of gig-workers are part-time workers.

- Gig-workers in app-based delivery services are largely young and male. Compared to employees in low-skilled occupations more generally, they are less likely to have German citizenship and more likely to have shorter employment periods and lower incomes.

Photo: makedonski2015/stock.adobe.com

DOI: 10.48720/IAB.FOO.20240709.01

Friedrich , Martin; Helm, Ines; Jost, Ramona; Lang, Julia; Müller, Christoph (2024)DOI: 10.48720/IAB.FOO.202407.09: Gig-work in the German delivery-services sector: Employment has increased significantly in recent years, In: IAB-Forum 9th of July 2024, https://iab-forum.de/en/gig-work-in-the-german-delivery-services-sector-employment-has-increased-significantly-in-recent-years/, Retrieved: 7th of March 2026

Diese Publikation ist unter folgender Creative-Commons-Lizenz veröffentlicht: Namensnennung – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de

Authors:

- Martin Friedrich

- Ines Helm

- Ramona Jost

- Julia Lang

- Christoph Müller

Martin Friedrich is a researcher in the department “Establishments and Employment” at the IAB.

Martin Friedrich is a researcher in the department “Establishments and Employment” at the IAB.  Prof Dr Ines Helm is a professor of economics at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Prof Dr Ines Helm is a professor of economics at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. Dr Ramona Jost is a researcher in the department " Active Labour Market Policies and Integration" at the IAB.

Dr Ramona Jost is a researcher in the department " Active Labour Market Policies and Integration" at the IAB. Julia Lang is a researcher in the department "Active Labour Market Policies and Integration" at the IAB.

Julia Lang is a researcher in the department "Active Labour Market Policies and Integration" at the IAB.  Christoph Müller is a researcher in the department "Active Labour Market Policies and Integration" at the IAB.

Christoph Müller is a researcher in the department "Active Labour Market Policies and Integration" at the IAB.