23. December 2024 | Labour Market, Employment and Social Policy

Subsidised jobs for the long-term unemployed: An evaluation of the German Participation Opportunities Act

Juliane Achatz , Frank Bauer , Jenny Bennett , Nadja Bömmel , Mustafa Coban , Martin Dietz , Kathrin Englert , Philipp Fuchs , Jan Gellermann , Claudia Globisch , Sebastian Hülle , Zein Kasrin , Peter Kupka , Anton Nivorozhkin , Christopher Osiander , Laura Pohlan , Markus Promberger , Miriam Raab , Philipp Ramos Lobato , Brigitte Schels , Maximilian Schiele , Mark Trappmann , Stefan Tübbicke , Claudia Wenzig , Joachim Wolff , Cordula Zabel , Stefan Zins

Two labour market programmes, ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ (‘Eingliederung von Arbeitslosen’ under section 16e of Book II of the German Social Security Code (SGB II)) and ‘Participation in the Labour Market’ (‘Teilhabe am Arbeitsmarkt’ under section 16i SGB II) – were introduced under the title of ‘Participation Opportunities Act’ (Teilhabechancengesetz) in 2019. Both programmes offer generous wage subsidies to employers from the private, public and non-profit sectors when they employ eligible long-term benefit recipients receiving basic income support for jobseekers. The subsidised job is intended to boost candidates’ social participation, employability and employment opportunities. The IAB evaluated the use and impact of the programmes between 2019 and 2023: its findings are described below.

Giving long-term unemployed people the opportunity to participate in working life through subsidised regular employment is the key achievement of the Participation Opportunities Act, which was introduced by the then German Government in 2018. At that time, the IAB, in a position paper written by Frank Bauer and colleagues, described the measures as an ‘important answer to the entrenching tendencies’ of unemployment and benefit-receipt. This assessment drew on the well-established finding that publicly-funded employment subject to social security contributions, despite its legal and institutional differences to market-based employment, significantly improves the social, material and cultural participation of participants.

Generous subsidies coupled with on-the-job support

Both programmes provide employers whose employment meets minimum- or union-wage standards with wage subsidies if they employ eligible candidates. ‘Participation in the Labour Market’ (§ 16i SGB II) targets very long-term unemployed people who are over 25 years old and have received basic income support for at least six of the last seven years. During this period, welfare recipients must have been jobless most of the time. Disabled people and people with at least one child in their household can receive support already after five years of receiving benefits. In the first two years, employers receive a subsidy of 100 percent of wages. In each additional year, the subsidy decreases by 10 percentage points and runs for a maximum of five years.

The programme ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ (§16e SGB II) is aimed at people who are somewhat closer to the labour market and have been unemployed for at least two years. The programme runs for two years and employers receive a subsidy of 75 percent of wages in the first year and 50 percent in the second.

On-the-job support is a key innovation in both programmes: Qualified on-the-job coaches provide participants with support at the start of and during the period of employment and help participants in dealing with personal as well as organisational challenges. A key aspect is the holistic approach to support: the coach takes the individual’s overall social context into account and not just direct employment-related issues. In the first six or twelve months, employers are obliged to give subsidised employees time for coaching. In addition, employees can gain qualifications and participate in further training measures during their subsidised employment.

A further innovation of the programme ‘Participation in the Labour Market’ (§ 16i SGB II) is the so-called ‘Passive-Active Transfer’ (PAT): here, jobcentres are reimbursed for a proportion of the passive benefits saved when a participant enters publicly funded employment. Jobcentres are reimbursed a flat rate which covers around a quarter of the funding costs. A recent increase in the flat rate of PAT has raised the proportion to 40 percent of funding costs.

Around 118,000 subsidised jobs have been generated since January 2019

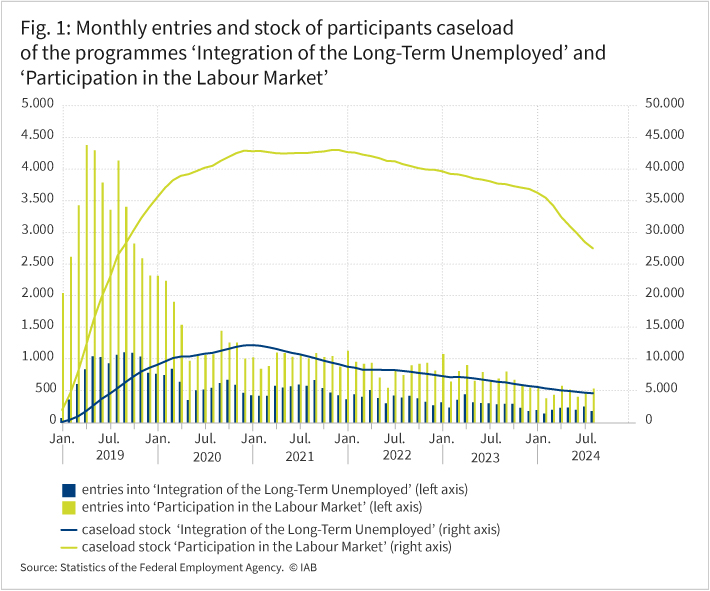

A large proportion of the subsidised employment relationships were generated in 2019, the first year of implementation. The amount of subsidised employment increased rapidly in the first nine months, and then started to decrease (see Figure 1).

Quantitative evidence based on interviews with relevant persons in the jobcentres shows that the majority of jobcentres welcomed the introduction of the programmes ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ and ‘Participation in the Labour Market’. The results also highlight that jobcentres attach greater importance to ‘Participation in the Labour Market’, as reflected in the higher level of subsidised employment generated using this instrument. When asked about the main objectives of the instruments, the jobcentres answered that the primary aim of ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ is the direct labour-market integration of participants. The majority of jobcentres hope for retention effects, i.e. the transfer of subsidised employees into a regular employment relationship with the same employer. In contrast, improving participants’ social participation plays a stronger role in the use of the programme ‘Participation in the Labour Market’.

Finally, financing is a central issue for the interviewed jobcentres. This is not particularly surprising, as both programmes are relatively cost-intensive – particularly Participation in the Labour Market’, which can entail a budgetary commitment for up to five years. The Passive-Active Transfer (PAT) therefore offers additional funding for this programme, especially for jobcentres with tight budgets, although PAT does not solve fundamental financial bottlenecks.

The programmes reach most target groups, although relevant subgroups remain underrepresented

The evidence from the evaluation highlights that those supported through ‘Participation in the Labour Market’ are particularly remote from the labour market relative to welfare recipients overall. This becomes evident in that older welfare recipients and welfare recipients who have not gained any work-experience at all within the last seven years are overrepresented among the participants. On the other hand, in relation to the comparison group, women, people without professional qualifications and people without German citizenship are underrepresented groups.

In contrast, participants in ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ are, in terms of their employment opportunities, roughly in the ‘middle’ compared to unemployed welfare recipients overall. This is in line with the envisioned target group of the programme ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’, whose primary aim is the labour-market integration of participants. Nevertheless, the analysis shows that the cohort of participants is a slightly positively selected group in relation to all eligible candidates. This is an indication of a cream-skimming of candidates, which could be due to the broader access criteria of ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ and to the stronger focus on the integration of previously subsidised individuals into unsubsidised employment as the main goal of the programme.

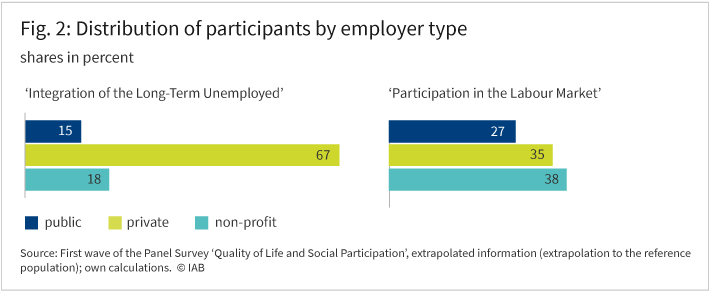

‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ is primarily used in the private sector; ‘Participation in the Labour Market’ is distributed more evenly across sectors

The sectors of employment within which participants are employed differ significantly between the two programmes. Whilst two thirds of people supported by ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ are employed by private companies, this applies to less than one in three people supported by ‘Participation in the Labour Market’. As Figure 2 shows, the proportion of non-profit employers is the highest for ‘Participation in the Labour Market’ at 38 percent while employment in the public sector is the least common at 27 percent. When it comes to ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’, public-sector (15 percent) and non-profit employers (18 percent) are at roughly similar levels and together account for one third of total employment. These differences may reflect that those supported by ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ are closer to the regular labour market.

On-the-job coaching is widely welcomed, but its practical implementation could be improved

The evaluation concludes that the combination of subsidised employment with on-the-job coaching is a key innovation within the portfolio of support-programmes for recipients of basic income support for jobseekers. Coaching takes the individual problems of participants into account and stabilises the employment relationship. As such, it represents an essential new tool in the job-integration process.

A quantitative evaluation based on the Panel Survey Quality of Life and Social Participation’ found that the majority of participants in the programmes received holistic on-the-job support (coaching), although coverage could be improved for ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’. Moreover, the results showed that coaching addressed a broad range of individual as well as employment-related issues. On average, the participants were satisfied with the coaching programme. Results from the evaluation’s qualitative case studies emphasise the importance of accounting for candidates’ limited employability and the adaption of employers’ expectations on performance- and behavioural-requirements. The employment integration of participants in both programmes is sometimes accompanied by serious crises and problems. In this context, it is particularly problematic that in some of the cases examined, participants’ obvious needs for support were not identified by coaches and, as a result, not addressed. Such unrecognised problems represent one of the main risks for the stability of the supported employment relationships and thus affect the central task of coaching.

Both instruments have a positive effect on the social participation of participants and their employability, but for ‘Participation in the Labour Market’ the effects weaken over time

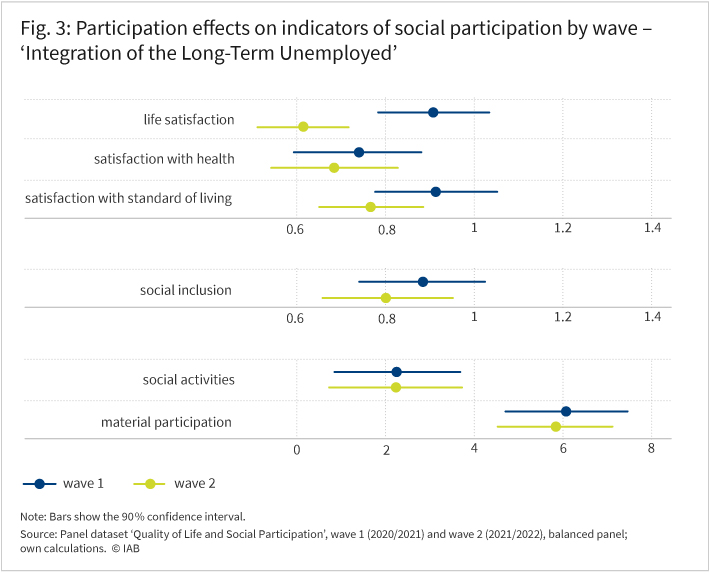

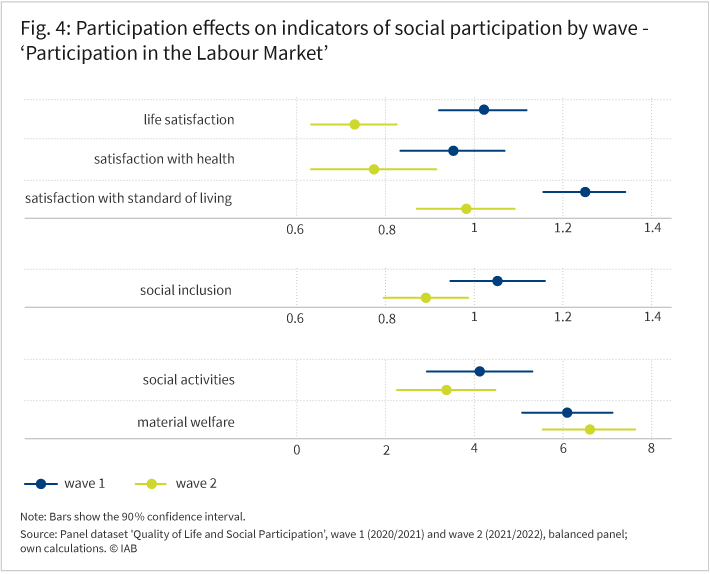

Given the negative social and employability effects of protracted unemployment, a key aim of both programmes is the improvement of participants’ social participation and employability. The evaluation shows that the subsidised employment has a significant positive effect on participants’ individual assessment on life satisfaction, social inclusion, social activities, material welfare as well as other subjective indicators compared to the control group of non-participants (see Figures 3 and 4).

Both programmes also have a significantly positive effect on various dimensions of employability, particularly on participants’ self-confidence, sense of control and performance-motivation. However, there is no evidence for an impact on the social capital of participants and on their social skills. Overall, the positive effect on social participation was especially high for men, persons living in single households, older persons and those in full-time employment.

Moreover, the effects were generally higher for participants employed in the public sector compared to those in the private sector. The fact that the positive effects decrease in the second survey wave could be due to a habituation effect. A further explanation could be that as the employment contract approaches its end for some of the participants surveyed, uncertain prospects for further employment and stressful working conditions can have a negative impact on life-satisfaction and health.

The programme ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ has a significant positive effect on the probability of participants taking up regular unsubsidised employment

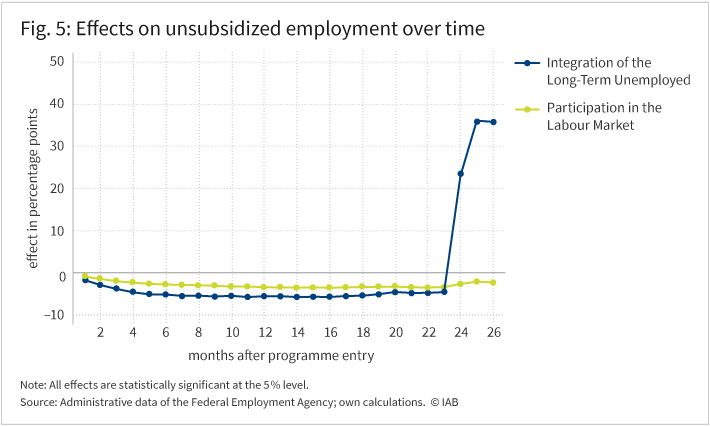

Using administrative data on participants and their employment characteristics, the impact analysis assessed, amongst other things, the effect of programme participation on the probability of entering regular unsubsidised employment up to 26 months after programme entry (see Figure 5). Participants in both programmes had a lower probability of entering regular employment compared to their comparison groups of non-participants in the first 23 months after entry into the programme. These negative employment effects are also referred to as lock-in effects, since participation in the subsidy programme reduces the probability that participants will look for or take up a regular job. However, compared to the largest predecessor wage subsidy programme (the employment subsidy or ‘Beschäftigungszuschuss’ ), these lock-in effects are relatively small. Upon expiry of the subsidy period under ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployment’, the negative employment effects turn positive.

After 26 months, previous participants in the programme have a 36-percentage point higher probability of entering regular employment compared to their comparison group. This effect is remarkable and significantly exceeds the effects measured for participants of the predecessor programme. Additional descriptive analyses show that a significant share of those in regular employment after expiry of the subsidy are working for the same employer they worked with during the subsidy period, highlighting a positive retention effect. In the case of ‘Participation in the Labour Market’, minor lock-in effects can still be observed at the end of the observation period (after 26 months). This is primarily because around 70 percent of the access cohort considered were still in funded employment at this point in time, due to the longer funding period of the instrument.

Both instruments reduce the benefit-receipt rates of participants, but in the case of ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ the effect declines over time

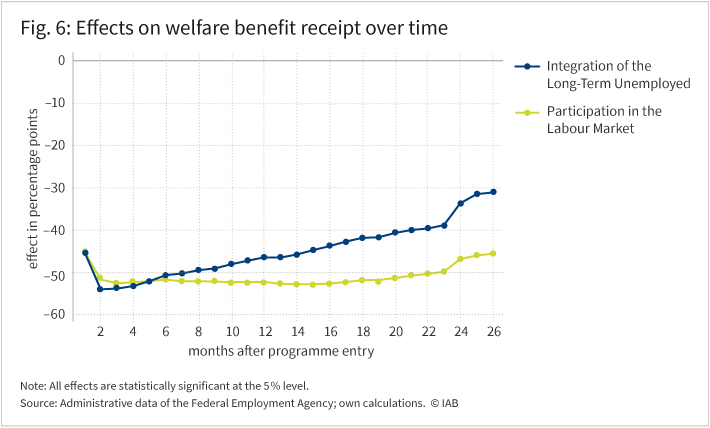

Closely linked to the goal of (re)integrating participants into the general labour market is the more fiscally-motivated goal of overcoming, or at least reducing, welfare dependency. With regard to the effect of the programmes on benefit-receipt status, the reduction in welfare dependency is highest in the first months of the programme for both instruments and tends to decrease over the observation period (in absolute terms). In the case of ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’, the level of benefit-receipt is initially 50 percentage points lower for participants than for the comparison group; after 26 months the effect drops to around 30 percentage points (see Figure 6). In the case of ‘Participation in the Labour Market’, the effects are much more stable and fall to around 45 percentage points in absolute terms after 26 months. This is not particularly surprising since, at the end of the observation period, the majority of those receiving support are still in subsidised employment and earning an income and therefore, relatively speaking, are less likely to require welfare.

Conclusion

The Participation Opportunities Act not only recognises and addresses the manifest socio-political problem of long-term unemployment and its associated effects of social exclusion and entrenched benefit-dependency, but also — based on findings so far — tackles it effectively. In addition to the positive social-participation effects of both instruments, the programmes by and large reach their target group. ‘Integration of the Long-Term Unemployed’ also has a positive effect on the transition into unsubsidised employment, at least in the short term. This programme therefore appears to have the potential to build a bridge for participants from unemployment to regular employment and at the same time to sustainably improve their social participation. For ‘Participation in the Labour Market’, it is still too early to evaluate effects on unsubsidised employment, given the long support-period of the programme.

So far, no undesirable side-effects — such as deadweight-, substitution- or displacement-effects — have been identified. These had been considered as risks, given that the programmes are available to employers in the private sector, and given the relatively generous subsidy-levels.

But: The success of both instruments can only be secured through adequate funding. Without reliable and appropriate financing, the legal existence of such instruments is of little value. Despite the current uncertainties in Germany’s federal budget, stable financing is needed for the use of these longer-term instruments. It is most unlikely that the employment effects of the more cost-intensive instrument, ‘Participation in the Labour Market’ (§ 16i SGB II) will be strong enough to amortise the costs incurred through future benefit-savings and tax-receipts.

This is an unrealistic scenario for the target group of six-year-plus in benefit receipt. However, it is also true that long-term exclusion from the labour market is associated with a manifold of individual and social problems — such as health impacts, isolation and withdrawal from social life and the intergenerational transmission of social inequality — that result in significant public and social costs. From an overarching societal perspective, the financing of subsidised employment can be a worthwhile investment in preventing the emergence of further social problems.

In brief

- With the Participation Opportunities Act, the funding portfolio of basic security for job seekers was expanded to include the funding instruments ‘Inclusion of the Long-Term Unemployed’ (Section 16e SGB II) and ‘Participation in the Labour Market’ (Section 16i SGB II).

- The IAB scientifically evaluated both instruments between 2019 and 2023. The focus was on the implementation of the instruments by the jobcentres, their operational use and their effect on the social participation, employability and labour market outcomes of those supported.

- The present findings show that both instruments largely reach their target groups reliably and have a positive effect on the various target dimensions. Due to the comparatively short observation period, no statements can be made about the stability of the effects. This also applies to the labour market impact of the instrument ‘Participation in the Labour Market’.

- The research results imply only moderate changes to the legal structure of the two instruments, but in some cases call for a more consistent implementation of existing regulations. Legal changes include, but are not limited to, the definition of the target group for ‘Inclusion of the Long-Term Unemployed’; implementation-based changes relate primarily to the job centres’ allocation practices in the case of ‘Participation in the Labour Market’, as well as the provision of on-the-job-coaching for both instruments.

- In view of increasing long-term unemployment and entrenched benefit receipt, instruments such as those in the Participation Opportunities Act will remain indispensable in the future in order to enable the affected group of people to participate in the labour market.

Literature

Achatz, Juliane et al. (2024): Evaluation des Teilhabechancengesetzes – Abschlussbericht. IAB-Forschungsbericht Nr. 4.

Bauer, Frank; Bennett, Jenny; Fuchs, Philipp; Gellermann, Jan F.C. (2023): Handlungsfelder und Anpassungsbedarfe der ganzheitlichen beschäftigungsbegleitenden Betreuung im Teilhabechancengesetz. In: Sozialer Fortschritt, Nr. 9/10, S. 731-746.

Bauer, Frank; Fuchs, Philipp; Gellermann, Jan F. C. (2022): Ganzheitliche beschäftigungsbegleitende Betreuung: vielfältiger Bedarf und hohe Anforderungen. In: Archiv für Wissenschaft und Praxis der Sozialen Arbeit, Nr. 4, S. 40-51.

Osiander, Christopher; Ramos Lobato, Philipp (2022): Bürgergeld-Reform: Deutliche Mehrheit der Jobcenter befürwortet die Entfristung des Förderinstruments „Teilhabe am Arbeitsmarkt“. IAB-Forum, 27.10.2022.

Raab, Miriam (2023): Mehr Teilhabe durch geförderte Beschäftigung? Die Perspektive der Geförderten. IAB-Forum, 28.09.2023.

Bild: PantherMedia / peshkova

DOI: 10.48720/IAB.FOO.20241223.01

Achatz, Juliane; Bauer, Frank; Bennett, Jenny; Bömmel, Nadja; Coban, Mustafa; Dietz, Martin; Englert, Kathrin; Fuchs, Philipp; Gellermann, Jan ; Globisch, Claudia; Hülle, Sebastian; Kasrin, Zein; Kupka, Peter ; Nivorozhkin, Anton; Osiander, Christopher; Pohlan, Laura; Promberger, Markus ; Raab, Miriam; Ramos Lobato, Philipp; Schels, Brigitte ; Schiele, Maximilian; Trappmann, Mark ; Tübbicke, Stefan; Wenzig, Claudia; Wolff, Joachim; Zabel, Cordula; Zins, Stefan (2024): Subsidised jobs for the long-term unemployed: An evaluation of the German Participation Opportunities Act, In: IAB-Forum 23rd of December 2024, https://iab-forum.de/en/subsidised-jobs-for-the-long-term-unemployed-an-evaluation-of-the-german-participation-opportunities-act/, Retrieved: 11th of March 2026

Diese Publikation ist unter folgender Creative-Commons-Lizenz veröffentlicht: Namensnennung – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de

Authors:

- Juliane Achatz

- Frank Bauer

- Jenny Bennett

- Nadja Bömmel

- Mustafa Coban

- Martin Dietz

- Kathrin Englert

- Philipp Fuchs

- Jan Gellermann

- Claudia Globisch

- Sebastian Hülle

- Zein Kasrin

- Peter Kupka

- Anton Nivorozhkin

- Christopher Osiander

- Laura Pohlan

- Markus Promberger

- Miriam Raab

- Philipp Ramos Lobato

- Brigitte Schels

- Maximilian Schiele

- Mark Trappmann

- Stefan Tübbicke

- Claudia Wenzig

- Joachim Wolff

- Cordula Zabel

- Stefan Zins

Juliane Achatz is a senior researcher in the research department „Joblessness and Social Inclusion“ at the IAB.

Juliane Achatz is a senior researcher in the research department „Joblessness and Social Inclusion“ at the IAB. Since 2004 the sociologist Dr Frank Bauer has belonged to the research staff of IAB North Rhine-Westphalia.

Since 2004 the sociologist Dr Frank Bauer has belonged to the research staff of IAB North Rhine-Westphalia. Dr Jenny Bennett has worked at ISG since May 2009 and is primarily engaged in the evaluation and monitoring of economic and social policies.

Dr Jenny Bennett has worked at ISG since May 2009 and is primarily engaged in the evaluation and monitoring of economic and social policies. Dr Nadja Bömmel has been a research associate in the „Labour Market and Social Security Panel“ research area at the IAB since February 2023.

Dr Nadja Bömmel has been a research associate in the „Labour Market and Social Security Panel“ research area at the IAB since February 2023. Dr Mustafa Coban has been leading the online survey "Work and Life in Germany" (IAB-OPAL) since 2023.

Dr Mustafa Coban has been leading the online survey "Work and Life in Germany" (IAB-OPAL) since 2023.  Since January 2012 Dr Martin Dietz has been Head of the staff unit „Research Coordination“ at Institute for Employment Research.

Since January 2012 Dr Martin Dietz has been Head of the staff unit „Research Coordination“ at Institute for Employment Research. Former IAB researcher Dr Kathrin Englert currently works at the Center for Evaluation and Policy Advice (ZEP) in Berlin.

Former IAB researcher Dr Kathrin Englert currently works at the Center for Evaluation and Policy Advice (ZEP) in Berlin. Dr Philipp Fuchs is Managing Director of the Institute for Social Research and Social Policy. He heads the „Labour Market Policy“ department.

Dr Philipp Fuchs is Managing Director of the Institute for Social Research and Social Policy. He heads the „Labour Market Policy“ department. Dr Jan Gellermann is part of the IAB’s Regional Research Network North Rhine-Westphalia.

Dr Jan Gellermann is part of the IAB’s Regional Research Network North Rhine-Westphalia. Dr Zein Kasrin's study majors were in economics, finance and IT. She has been working as a researcher at the IAB since August 2020.

Dr Zein Kasrin's study majors were in economics, finance and IT. She has been working as a researcher at the IAB since August 2020. Dr Peter Kupka has been with the IAB since 2002 and is a research assistant in the „Research Coordination“ Unit at the IAB.

Dr Peter Kupka has been with the IAB since 2002 and is a research assistant in the „Research Coordination“ Unit at the IAB. Dr Anton Nivorozhkin is senior researcher in the department „Joblessness and Social Inclusion“ at the IAB.

Dr Anton Nivorozhkin is senior researcher in the department „Joblessness and Social Inclusion“ at the IAB. Since 2009 Dr Christopher Osiander has been a researcher at the IAB, currently at the Department of Research Coordination.

Since 2009 Dr Christopher Osiander has been a researcher at the IAB, currently at the Department of Research Coordination. Dr Laura Pohlan is a researcher in the research department „Labour Market Processes and Institutions” at the IAB and at ZEW’s Research Group „Market Design”.

Dr Laura Pohlan is a researcher in the research department „Labour Market Processes and Institutions” at the IAB and at ZEW’s Research Group „Market Design”. Prof Dr Markus Promberger heads the departement „Joblessness and Social Inclusion“ and is working on projects on labour migration.

Prof Dr Markus Promberger heads the departement „Joblessness and Social Inclusion“ and is working on projects on labour migration. Since 2018, Miriam Raab has been a researcher at the research department „Joblessness and Social Inclusion” at the IAB.

Since 2018, Miriam Raab has been a researcher at the research department „Joblessness and Social Inclusion” at the IAB. Dr Philipp Ramos Lobato has been a researcher at the IAB since November 2008.

Dr Philipp Ramos Lobato has been a researcher at the IAB since November 2008. Since 2024 Brigitte Schels has been Professor of Empirical Social Structure Analysis at the Paris Lodron University of Salzburg.

Since 2024 Brigitte Schels has been Professor of Empirical Social Structure Analysis at the Paris Lodron University of Salzburg. Currently Dr Maximilian Schiele works as a reasercher at the Institute for Employment Research in Nuremberg.

Currently Dr Maximilian Schiele works as a reasercher at the Institute for Employment Research in Nuremberg. Prof Dr Mark Trappmann is head of the research department „Panel Study Labour Market and Social Security“.

Prof Dr Mark Trappmann is head of the research department „Panel Study Labour Market and Social Security“. Dr Stefan Tübbicke has been working as a post-doc at the IAB in the research area „Basic Income Support and Activation” since October 2020.

Dr Stefan Tübbicke has been working as a post-doc at the IAB in the research area „Basic Income Support and Activation” since October 2020. Dr Claudia Wenzig joined IAB as a researcher in December 2005 and is part of the department „Panel Study Labour Market and Social Security“.

Dr Claudia Wenzig joined IAB as a researcher in December 2005 and is part of the department „Panel Study Labour Market and Social Security“. PD Dr Joachim Wolff has been head of the IAB Research Unit „Basic Income Support and Activation“ since July 2005.

PD Dr Joachim Wolff has been head of the IAB Research Unit „Basic Income Support and Activation“ since July 2005. Socylogist Dr Cordula Zabel has been joining the Institute for Employment Research as a researcher in January 2008.

Socylogist Dr Cordula Zabel has been joining the Institute for Employment Research as a researcher in January 2008. Since April 2019, Dr Stefan Zins has been working as a specialist in the „Statistical Methods Department at the IAB“.

Since April 2019, Dr Stefan Zins has been working as a specialist in the „Statistical Methods Department at the IAB“.