25. March 2025 | Labour Market Policy

The unexpected effects of the German minimum wage on income equality in firms

The minimum wage has been regarded as an important policy measure to address income disparities between low-wage and high-wage workers. These disparities arise both because some firms pay more than other firms (i.e. between firm inequality) and because some employees earn more than other employees within the same firm (i.e. within firm inequality). The minimum wage is regarded as an important policy tool to address income disparities between low-wage and high-wage workers.

A recent study by Hamzeh Arabzadeh et al. found that Germany’s introduction of a minimum wage in 2015 successfully reduced within firm inequality. As one would expect, the primary reason is that minimum wages raise the earnings of low-wage workers for whom the minimum wage is binding. However, at the same time, what is less understood is that minimum wage policies also have consequences for high-wage workers.

The reduction in wage inequality within firms varies widely and is much greater in firms with financial constraints, such as low assets, high debt, or limited cash reserves. These firms often pay lower wages, requiring bigger increases for low-wage workers when the minimum wage rises. At the same time, they tend to give smaller raises to high earners or lose them to better-paying jobs. As a result, a firm’s financial health or aggregate financial conditions significantly influences how effectively minimum wage policies reduce wage inequality.

The minimum wage in Germany

Germany introduced a statutory minimum wage on 1 January 2015, setting an hourly gross wage of at least 8.50 euro. This policy affected up to a quarter of German employees, as many were earnings below or near this threshold before its implementation. By design, a minimum wage establishes a wage floor, reducing wage inequality at the lower end of the wage distribution. However, a minimum wage can also have broader effects that affect higher wage workers due to changes in a firm’s staffing decisions as well as overall employment levels.

For these reasons, the effect of a minimum wage on inequality is not straightforward. Previous research indicated that the introduction of Germany’s minimum wage increased wages overall, had little to no negative impact on employment, and reduced wage inequality. This article focuses on how firms’ financial constraints influence wage inequality within firms after the minimum wage introduction. Measures are developed to assess the extent to which firms were affected by the minimum wage and the level of financial constraints they faced.

Defining the measures

1. Firms’ exposure to the minimum wage: minimum wage bite

The measure of “minimum wage bite” is the extent to which a firm’s wage structure is impacted by the need to raise wages to meet the new minimum wage. A high minimum wage bite indicates that a firm faces a significant increase in personnel costs. This is typically the case when a large proportion of employees previously earned below the minimum wage or when their wages were far below the new threshold. For instance, if all employees in a firm earned 7.23 euro per hour before 2015, the bite would be calculated as a 15 percent increase in wages needed to meet the 8.50 euro minimum. In essence, the minimum wage bite represents the relative increase in a firm’s wage bill required to bring all workers up to the minimum wage level.

2. Firms’ financial constraints: financial leverage

Financial constraints are a firm’s ability to access external financial resources that may be used to invest, hire, or adjust wages when policies like minimum wage increases are introduced. We measure financial constraints using leverage, calculated as the ratio of a firm’s total debt (current and long-term liabilities) to its total assets. For example, a leverage ratio of 50 percent means a firm’s total debt equals half of its assets, with higher ratios indicating greater reliance on external financing. In our data, around 30 percent of firms had leverage ratios above 50 percent before the minimum wage introduction, which we use as a threshold to classify firms as financially constrained.

3. Wage inequality within firms: wage dispersion

There are three ways to measure within firm wage inequality. One is the 90/10 ratio or the difference between the top (90th percentile) of the within firm wage distribution compared to the bottom (10th percentile). We also examine the disparities between high and median earners (90th to 50th percentile) and between median and low earners (50th to 10th percentile). In each case, a larger gap indicates greater inequality and, together, these measures represent within firm wage distribution.

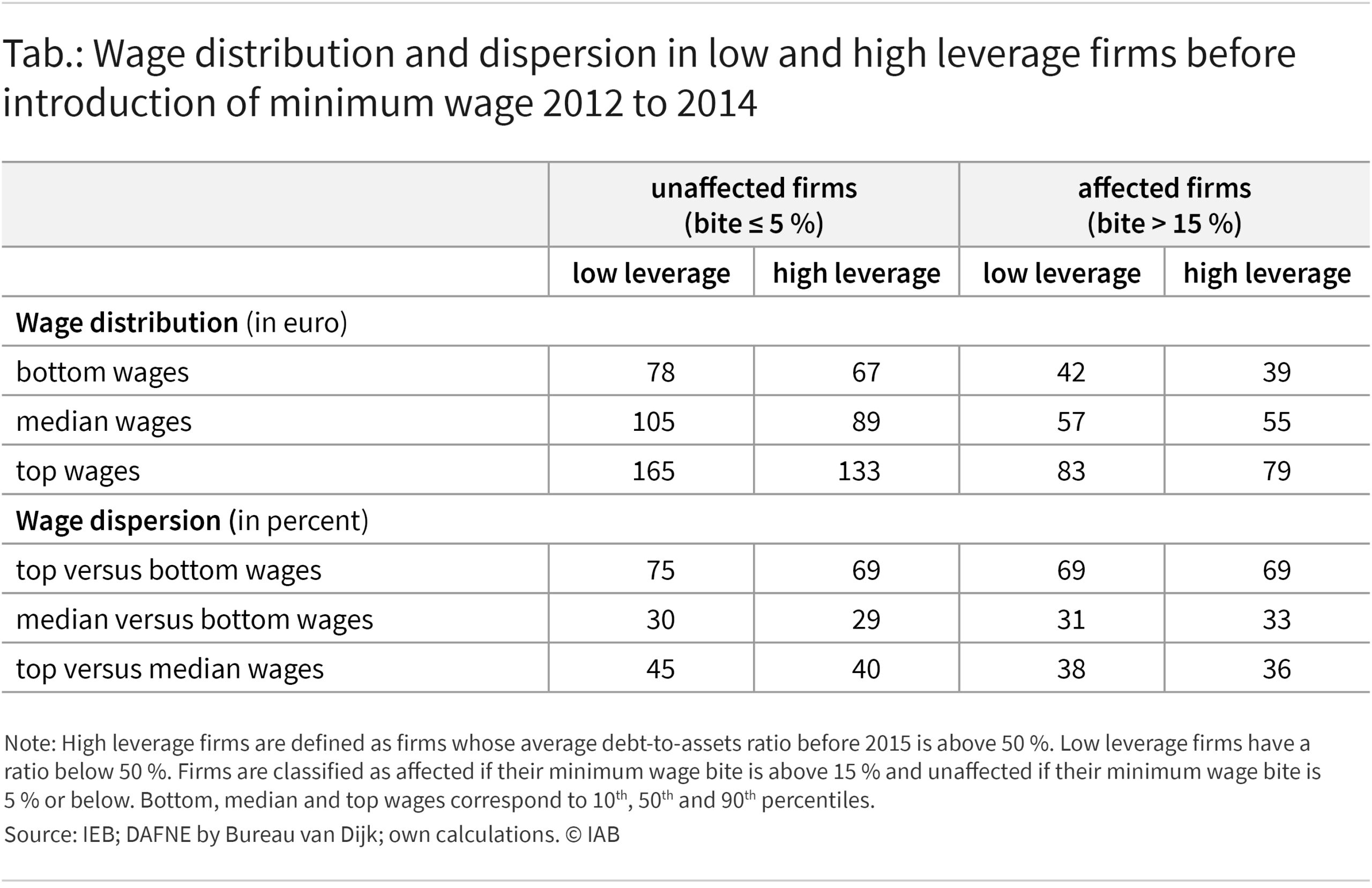

Wage distribution and wage dispersion before minimum wage

Before the introduction of the minimum wage (2012–2014), wage levels and dispersion varied across firms depending on their exposure to the policy and their financial constraints. Firms classified as affected had a minimum wage bite above 15 %, while unaffected firms had a bite of 5 % or below. Financial constraints were also a key factor, with high-leverage firms having an average debt-to-assets ratio above 50 % before 2015, while low-leverage firms remained below this threshold (see Table 1).

Unaffected firms tend to have higher average wages and greater wage dispersion, driven mainly by larger gaps at the top end of the wage distribution (90th–50th percentiles). In contrast, high-leverage firms generally offer lower wages across the entire distribution and do not exhibit greater wage dispersion in either group. The summary statistics in table 1 highlight that financial constraints shape wage structures differently across firms in the period before the introduction of the minimum wage.

How do financial constraints affect wage dispersion?

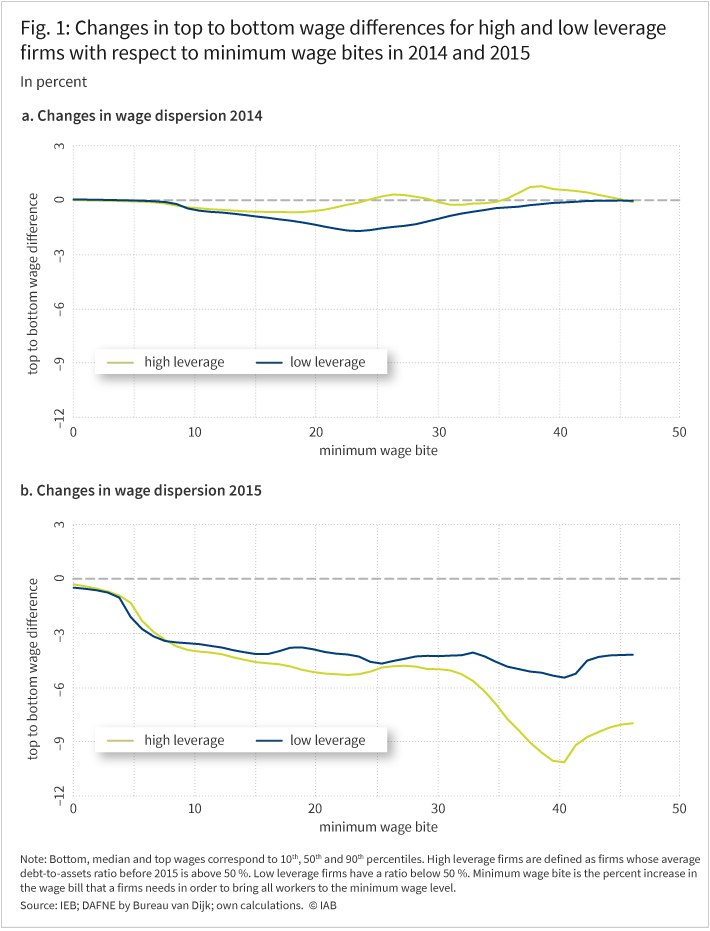

The introduction of the minimum wage in 2015 altered the relationship between financial constraints and wage inequality. As the minimum wage bite increased, wage inequality within firms declined, with the reduction being even more pronounced in financially constrained firms. In contrast, no clear differences in wage inequality by minimum wage bite or financial constraints were observed in 2014, before the policy was implemented (see Figure 1).

Controlling for alternative explanations

There are other possible explanations than the financial strength of a firm for the observed decline in inequality. We highlight three. One is that low-wage workers often experience faster wage growth than high-wage workers. This could occur independently of minimum wage policies and may disproportionately affect firms with a high minimum wage bite that employ more low-wage workers. Another is that industry- or region-specific wage inequality trends could influence the results if they correlate with a firms’ minimum wage exposure or financial constraints. Finally, financial constraints (or leverage) could also shape wage inequality because they reflect underlying differences in firms’ productivity or growth strategies. To address these issues, a formal econometric model is used to control for firm specific factors, industry- or region-specific macroeconomic trends and alternative mechanisms, like productivity.

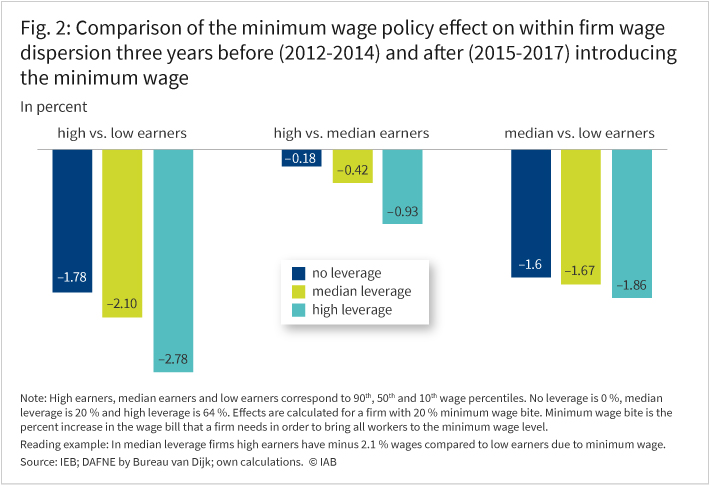

Effect of minimum wage policy on wage inequality

Examining the effect of minimum wage policy on wage inequality, results indicate that a firm experiences a 1.78 percentage point decline in 90/10 wage inequality with a 20 percent minimum wage bite and no financial constraints (see Figure 2, blue bar). If leverage increases to the median (20 %), a firm experiences a 2.1 percentage point decline in 90/10 wage inequality (green bar). If leverage is very high (90th percentile, 64 %), a firm experiences a 2.78 percentage point decline in 90/10 wage inequality (turquoise bar). Therefore, going from zero leverage to very high leverage reduces within firm wage inequality by 1 percentage point.

Most of the decline in wage dispersion induced by the minimum wage comes from the bottom part of the distribution (50/10 inequality): a firm with a 20 percent minimum wage bite experiences a decline in wage dispersion between median and low earner of 1.6 percentage points. By comparison, only a very small part of the decline in wage dispersion comes from the top of the distribution (90/50 inequality).

However, at the same time, a firm with a 20 percent minimum wage bite and no leverage experiences a 0.18 percentage point decline in top end inequality. By comparison, a firm with a similar wage bite and high leverage experiences a 0.93 percentage point decline in top end inequality. The interpretation is that financial constraints within firms play a more significant role in shaping wage inequality at the top of the distribution, with highly leveraged firms having a greater impact on higher earners.

One possible explanation is that financially constrained firms fail to increase wages of very high earners relative to the median earners. Alternatively, high-earner workers leave financially constrained firms for better job prospects. Either way, the broader point is that minimum wage policies not only affect low-wage workers, but they also affect high-wage earners in financially constrained firms.

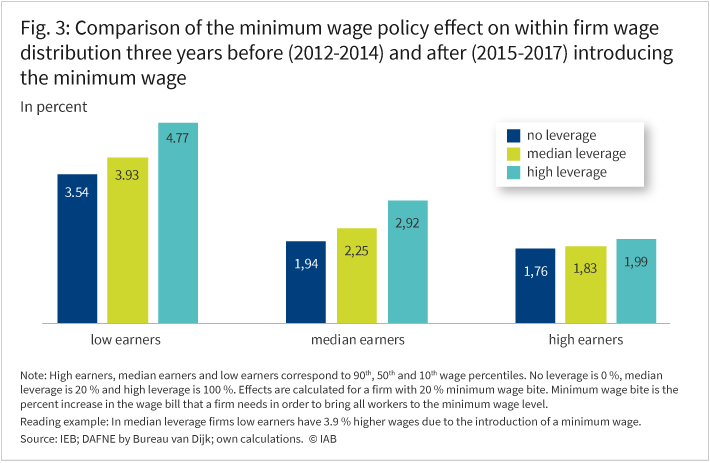

As expected, the policy primarily benefits low-wage earners, with the strongest effects at the bottom of the wage distribution. In firms with 20 percent minimum wage bite, wages at the 10th percentile rise by 3.54 percentage points, but in highly leveraged firms, this increase is even larger at 4.77 percentage points. Median earners also see gains, though to a lesser extent, with wages increasing by additional 0.98 percentage point in highly leveraged firms. For high earners, however, the difference between financially constrained and unconstrained firms narrows to just 0.98 percentage points (see Figure 3).

These patterns indicate that financially constrained firms, despite offering lower wages across the entire distribution, primarily raise wages for low- and middle-wage workers after the minimum wage introduction. Importantly, these findings account for changes in employment, meaning the wage increases reflect not only raises for existing workers but also shifts in who is hired or let go. Therefore, financial constraints shape how firms adjust to wage regulations, influencing both pay structures and workforce composition across the wage distribution.

Conclusion

The introduction of Germany’s federal minimum wage was a significant policy shift, contributing to a reduction in wage inequality both within and across firms. The decline in wage dispersion was particularly pronounced in financially constrained firms. These firms, which employed a large share of low-wage workers, saw substantial reductions in inequality at the lower end of the wage distribution due to wage increases for low earners. At the upper end financially constrained firms experienced further declines in inequality. Some potential reasons are that they were unable to raise wages for high earners or lost these workers to better-paying opportunities. Overall, the findings indicate that a firm’s financial capacity plays a key role in shaping the outcomes of minimum wage policies.

Data

We combine three data sets:

IAB Integrated Employment Biographies (IEB): it is employee-level administrative data of all jobs covered by social security (excluding civil servants and the self-employed). This data includes daily gross wages (base wage plus extra pay) for each job of a worker in a given establishment.

Administrative hours data by Vom Berge et al. (2023): this provides job-level hours worked information between 2011 and 2014.

Bureau van Dijk’s Dafne: it compiles yearly financial accounts for public and private firms in Germany and allows us to measure firms’ financial strength. Dafne provides balance sheet information (e.g. total assets, long and short-term debt, cash holdings etc.) for a large set of firms.

In brief

- On 1 January 2015, Germany implemented a federal minimum wage of 8.50 euro per hour. This policy affected wages of a significant portion of the workforce, especially those earning below or around the minimum wage prior to its introduction.

- The introduction of a minimum wage reduced wage dispersion for firms that employed workers with wages below the minimum wage threshold, and especially among financially constrained firms.

- While most of the reduction in wage dispersion occurs at the bottom of the wage distribution (50/10 inequality), for financially constrained firms there is an additional, more pronounced effect at the top of the distribution (90/50 inequality).

- The results indicate that a firm’s financial situation plays an important role in how it responds to minimum wage policies, which can help policymakers predict how minimum wage increases affect workers’ pay and firms’ ability to adapt.

Literature

Arabzadeh, Hamzeh; Balleer, Almut.; Gehrke, Britta; Taskin, Ahmet Ali (2024): Minimum wages, wage dispersion and financial constraints in firms. European Economic Review, No. 163, Art. 104678.

Bossler, Mario; Hans-Dieter Gerner (2020): “Employment effects of the new German minimum wage: Evidence from establishment-level microdata.” ILR review. Vol. 73, No. 5, pp. 1070-1094.

Bossler, Mario, and Schank, Thorsten (2023): Wage inequality in Germany after the minimum wage introduction. Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 41, No. 3, pp. 813-857.

Dustmann, Christian., Lindner, Attila.; Schönberg, Uta; Umkehrer, Matthias; vom Berge, Philipp (2022): Reallocation effects of the minimum wage. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 137, No. 1, pp. 267-328.

Link, Sebastian (2024): “The price and employment response of firms to the introduction of minimum wages.” Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 239, Art. 105236.

Vom Berge, Philipp; Umkehrer, Matthias; Wanger, Susanne (2023): A correction procedure for the working hours variable in the IAB employee history. Journal for Labour Market Research, Vol. 57, No. 1, pp. 1-16.

picture: elmar gubisch/stock.adobe.com

DOI: 10.48720/IAB.FOO.20250325.02

Gehrke, Britta; Taskin, Ahmet Ali (2025): The unexpected effects of the German minimum wage on income equality in firms, In: IAB-Forum 25th of March 2025, https://iab-forum.de/en/the-unexpected-effects-of-the-german-minimum-wage-on-income-equality-in-firms/, Retrieved: 9th of March 2026

Diese Publikation ist unter folgender Creative-Commons-Lizenz veröffentlicht: Namensnennung – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de

Authors:

- Britta Gehrke

- Ahmet Ali Taskin

Prof Dr Britta Gehrke has been Professor of Macroeconomics at Freie Universität Berlin since April 2023.

Prof Dr Britta Gehrke has been Professor of Macroeconomics at Freie Universität Berlin since April 2023. Ahmet Ali Taskin, Ph. D., is a senior researcher in the Forecasts and Macroeconomic Analyses (MAKRO) research area at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB).

Ahmet Ali Taskin, Ph. D., is a senior researcher in the Forecasts and Macroeconomic Analyses (MAKRO) research area at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB).