29. August 2025 | Structural Change and the Labour Market

Gender convergence in all areas: Is it a myth?

Over the past few decades, there is increasing convergence between men’s and women’s employment rates, hours worked, pay, and occupational representation in most developed countries. One of the most important reasons is rising female labour force participation during the second half of the 20th century. Despite this progress, women continue to face persistent forms of inequality, particularly in occupational choices, pay, and opportunities for promotion.

Stubborn gender inequality

There is general agreement that the majority of the remaining gender employment gap stems from income losses associated with motherhood. Following the birth of a first child, mothers experience significant reductions in earnings relative to fathers, largely due to lower rates of employment or part-time work – an effect commonly referred to as the “motherhood penalty.”

These penalties vary substantially across countries. They are lowest in the Nordic countries – for example, Denmark reports a 24 percent penalty – and highest in the German-speaking world, with penalties of 61 percent in Germany, 51 percent in Austria, and 68 percent in Switzerland. Although these countries score high in various gender equality indices (e.g. European Institute for Gender Equality), there exists a hidden source of inequality which particularly affect mothers. The question is why?

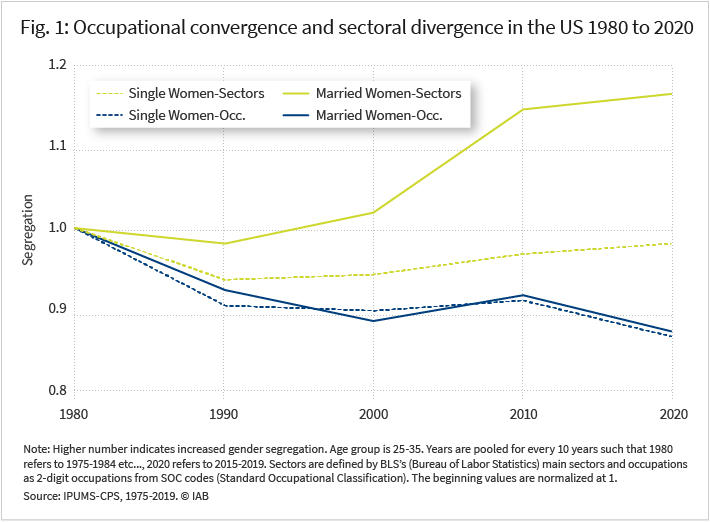

One possible explanation lies in the distinction between occupations and sectors (see info box): Even as women and men increasingly work in similar occupations, sectoral segregation has continued to rise. For example, Alon et al. (2025) showed that in the United States, sectoral segregation (men and women working in different sectors) has grown over time despite clear evidence of occupational convergence (see info box). This trend appears to be driven primarily by married women and mothers (see Figure 1).

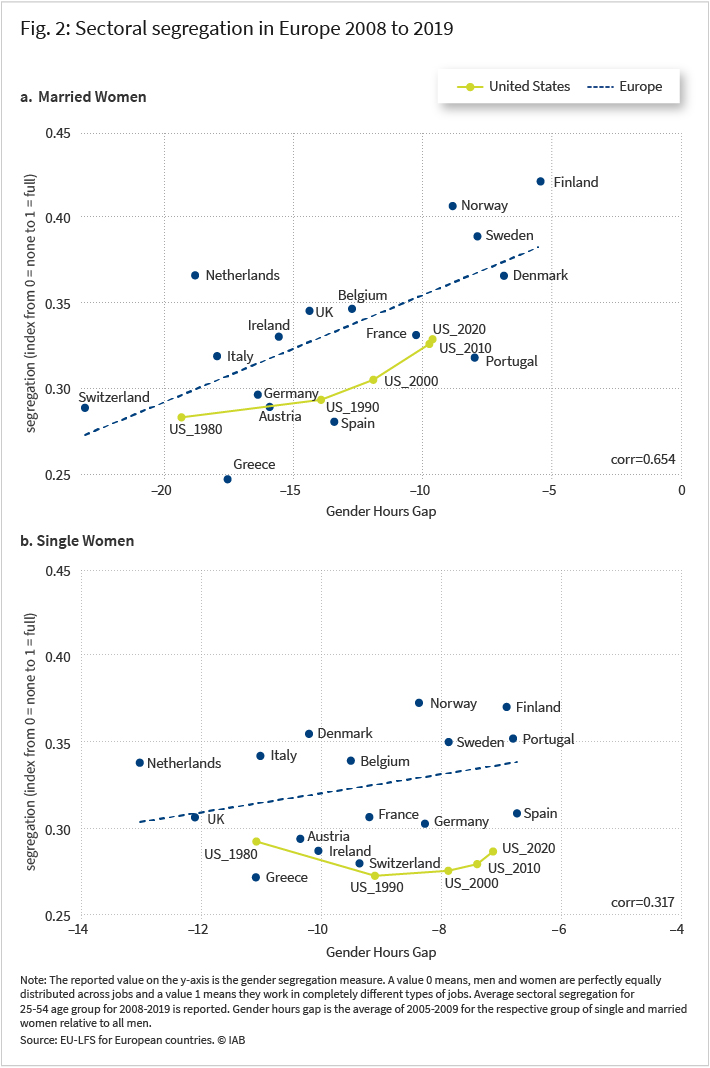

Since the 1980s, both single and married women have experienced similar levels of occupational convergence relative to men. Yet their sectoral choices have diverged: Single women now work in sectors similar to those of men, while married women are increasingly concentrated in female-dominated sectors. This sorting is even more pronounced in countries with greater gender equality, as measured by hours worked (see Figure 2).

In countries where women’s overall labour force participation is lower (i.e. where the gender hours gap is larger), the women who do work tend to be employed in sectors that resemble those of men, resulting in lower sectoral segregation. By contrast, in countries where gender equality is high across many dimensions, women – especially married women – are increasingly clustered in sectors such as education and health. This paradoxical pattern raises important questions about the drivers of gendered labour market outcomes.

The role of preferences and discrimination

The rise in sectoral segregation could stem from two broad factors: changing preferences or persistent discrimination. One possibility is that women – especially mothers – may place greater value on certain non-wage amenities, leading them to choose specific sectors even if they continue to face wage disadvantages. Alternatively, women are increasingly sorted into sectors where discrimination is lowest or has declined most over time.

To better understand the underlying forces behind rising sectoral segregation, research distinguishes between the roles of preferences and discrimination (Hsieh et al. 2019) by comparing relative wages and employment patterns of men and women across sectors (Alon et al. 2025). While the growth of female dominant service sectors such as health and education is responsible for part of the increase in sectoral segregation, changing preferences of women towards certain sectors accounts for the majority of the increase (59 %). Research indicates that sectoral preferences are correlated with part-time work and the number of children, suggesting that certain sector-specific amenities are especially appealing to women with (or planning to have) children. As a result, female preferences also drive gender inequality.

Supporting this interpretation, women often switch jobs before the birth of their first child, moving toward more female-dominated sectors such as education and healthcare (Coskun et al. 2023). These sectors tend to offer more predictable schedules, fewer demands for overtime, and earnings that are closely tied to the number of hours worked. They also typically feature lower returns to experience, lower risk, and overall lower pay. Women who go on to have more children are even more likely to change sectors after the birth of their first child, suggesting that fertility planning may prompt women to re-optimize their career paths early on.

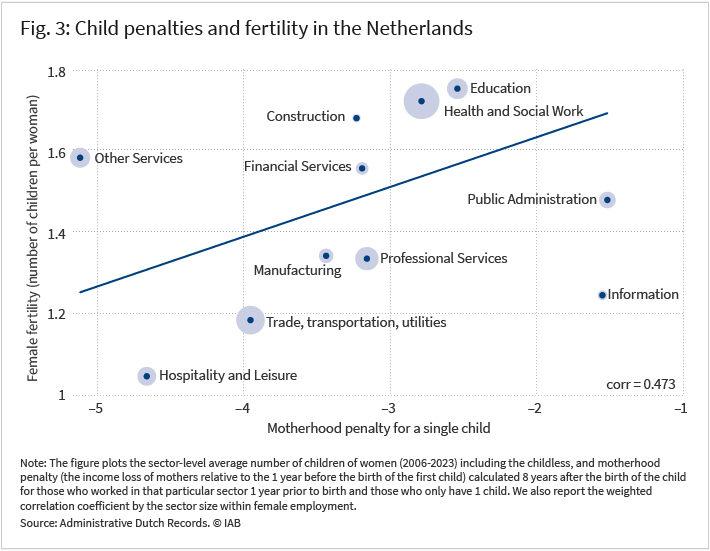

The self-selection among women into more family-friendly sectors reflects a desire to access workplace amenities that make it easier to combine work and caregiving or reduce the financial penalties associated with having children. For instance, in high-paying career tracks where pay grows sharply with experience and long hours, taking time off for childcare can result in substantial long-term earnings losses. In contrast, jobs with steadier pay progression and fewer penalties for time away may offer greater income stability for mothers. Indeed, when child penalties are calculated at the sector level, women in the Netherlands tend to have more children in sectors where the earnings loss per child is lower (see Figure 3). These findings highlight the complex links between women’s preferences, sectoral sorting, fertility choices, and gender inequality.

Trinity of “Work Job Children”

The result is a three-way trade-off. First is “childlessness”; i.e. women prefer staying childless in order to progress in their career. Second is “motherhood penalty”; i.e. labour market outcomes of women are potentially less similar to men in comparison to a world where the cost of children were equally shared between men and women. Third is “sectoral segregation”; sorting into particular types of jobs where the trade-off is less strict; i.e. sectoral amenities make combining work and motherhood more possible, but offer lower and flat pay schedule over life time.

Rising sectoral segregation might seem like a step backward for gender equality. However, the picture becomes more complex when we consider the underlying trade-offs. If we were to artificially impose a “more equal” distribution of men and women across sectors – without addressing the unequal burden of childcare and the variation in child penalties across sectors – the result could actually be a wider gender pay gap. In such a scenario, women might find themselves in sectors that offer less protection from the income losses associated with motherhood. Alternatively, fertility could decline even further if women are unable to shield themselves from these penalties by selecting into more family-friendly sectors.

Predicting which of these outcomes would prevail is far from straightforward. For example, fertility responses may be more negative in countries where child penalties are particularly high, while in groups with stronger fertility preferences, the impact might be negligible. What is clear is that today’s gender inequality largely stems from the difficult trade-off between career and motherhood. A path toward greater gender equality that does not come at the cost of falling fertility must involve not only more family-friendly policies, but also a more equal sharing of caregiving responsibilities between men and women.

Conclusion: Women face a rough trade-off

In conclusion, the gender gap in wages, employment, and hours is primarily due to motherhood. To protect themselves from large child penalties, women sort themselves into specific sectors based on their fertility preferences and observed sectoral amenities which might facilitate combining work and motherhood. Hence, women who participate in the labour market face a tough choice between having a child and pursuing a career job.

Definition of “occupation” and “sector”

An occupation is related to the task performed by an individual to produce a good whereas sector is related to the type of good produced. For instance, one can be a manager (occupation), either in a finance company or at a school (sector). Occupation is more directly related to the qualifications of an individual, hence educational attainment.

Data

- IPUMS-CPS (Current Population Survey) is used for the US and EU-LFS (European Labor Force Survey) for European Countries.

- Segregation measure is calculated by first calculating the employment share of each sectors/or occupation in total men’s and women’s employment. For each sector (occupation), the absolute value of the difference between men’s and women’s share is considered as sectoral contribution to the segregation. Half of the sum across all sectors is the overall segregation measure.

- Occupational segregation is calculated based on the employment share of each 2 digit occupation in men’s vs women’s total employment.

- Sectoral segregation is calculated based on 11 main sectors defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for the US and the corresponding match for the European Industry Classification (NACE).

- Administrative Dutch records are used for the calculation of sectoral level child penalties and fertility.

In Brief

- Despite occupational gender convergence, there is an increased sectoral gender segregation over time, especially among married women.

- In more gender equal countries, women work in more different sectors than men relative to less gender equal countries.

- The role of women’s preferences is larger than the role of discrimination for high degrees of sectoral segregation.

- Certain sectoral amenities such as part-time share and number of children as measures of family-friendliness correlate with high female preferences.

- Women switch sectors prior to the birth of first child towards more female dominant sectors, which offer lower child penalties, and those women have higher fertility rates.

- Without reducing motherhood penalties, artificially allocating women to the same jobs as men might result in either “lower pay”for or “lower fertility” of women.

Literature

Alon, Titan; Coskun, Sena; Olmstead-Rumsey, Jane (2025): “Gender Divergence in Sectors of Work.” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 20076.

Coskun, Sena; Dalgic, Husnu; Ozdemir, Yasemin (2023): “Child Penalties and Fertility across Sectors.” Working Paper.

Goldin, Claudia (2014): “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter.” American Economic Review 104 (4): 1091–1119.

Hsieh, Chang-Tai; Hurst, Erik; Jones, Charles I.; Klenow, Peter J. (2019): “The allocation of talent and U.S. economic growth.” Econometrica 87 (5): 1439–1474.

Kleven, Henrik; Landais, Camille; Leite-Mariante, Gabriel (2024): “The child penalty atlas.” Review of Economic Studies.

picture: wavebreak3/stock.adobe.com

DOI: 10.48720/IAB.FOO.20250829.02

Coskun, Sena (2025): Gender convergence in all areas: Is it a myth?, In: IAB-Forum 29th of August 2025, https://iab-forum.de/en/gender-convergence-in-all-areas-is-it-a-myth/, Retrieved: 28th of February 2026

Diese Publikation ist unter folgender Creative-Commons-Lizenz veröffentlicht: Namensnennung – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de

Authors:

- Sena Coskun

Jun.-Prof. Sena Coskun, PhD, has been a Junior Professor of Macroeconomics and Labor Market Research at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg.

Jun.-Prof. Sena Coskun, PhD, has been a Junior Professor of Macroeconomics and Labor Market Research at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg.